This article from the 2010 fall issue of Tustenegee was written by Richard “Tony” Marconi, former HSPBC Director of Education. For proper context, please note the original publication year of all reprinted articles here. They receive only minimal editing.

by Richard A. Marconi

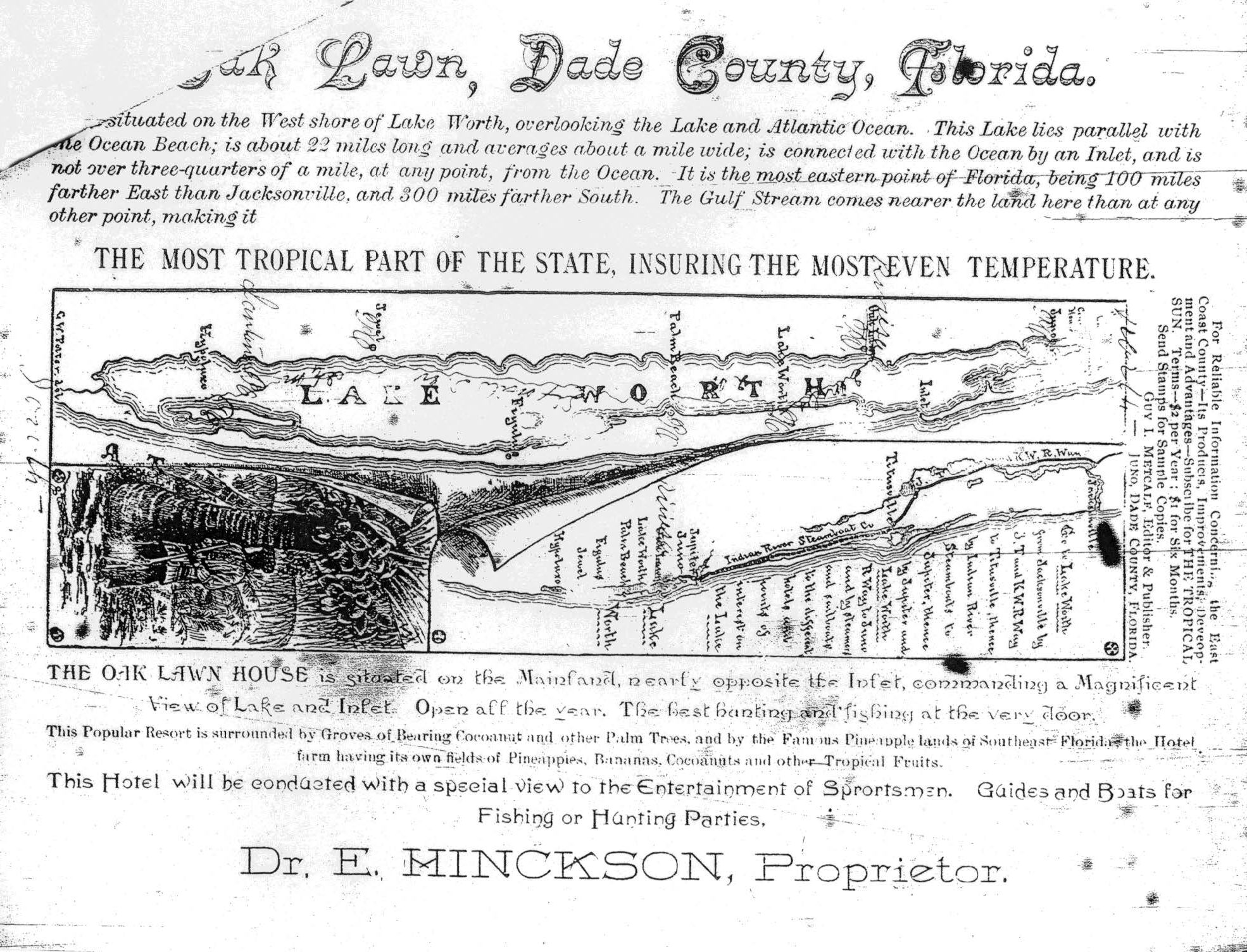

Part II is a continuation of “Three Early Hotels on Lake Worth I” in the spring 2010 issue of Tustenegee, which examined the Cocoanut Grove House (est. 1880), the first hotel opened on Lake Worth. This part is about Hotel Lake Worth and Oak Lawn House (both est. 1888).

“Best hotel in this part of Florida [Hotel Lake Worth].”

–William Drysdale of New York, 1891

Hotel Lake Worth

New Yorker Harlan Page Dye (1851-1930) came to the Lake Worth area in 1874 via Jacksonville. He had been traveling with friends to Kansas City when the group stopped at Lake Worth for a rest. When they were ready to resume their travels, Dye decided he was going to stay. He filed a land grant with the state and established a homestead north of the present Flagler Memorial Bridge on the east shore of the lake. A year later, he constructed the sloop Mohawk in Titusville to transport people, supplies, and mail to the lake region. Then, as assistant keeper at the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, Dye built another boat, the eleven-ton Gazelle, to transport the settlers’ produce to Jacksonville to sell and to bring passengers to Palm Beach on the return trip.

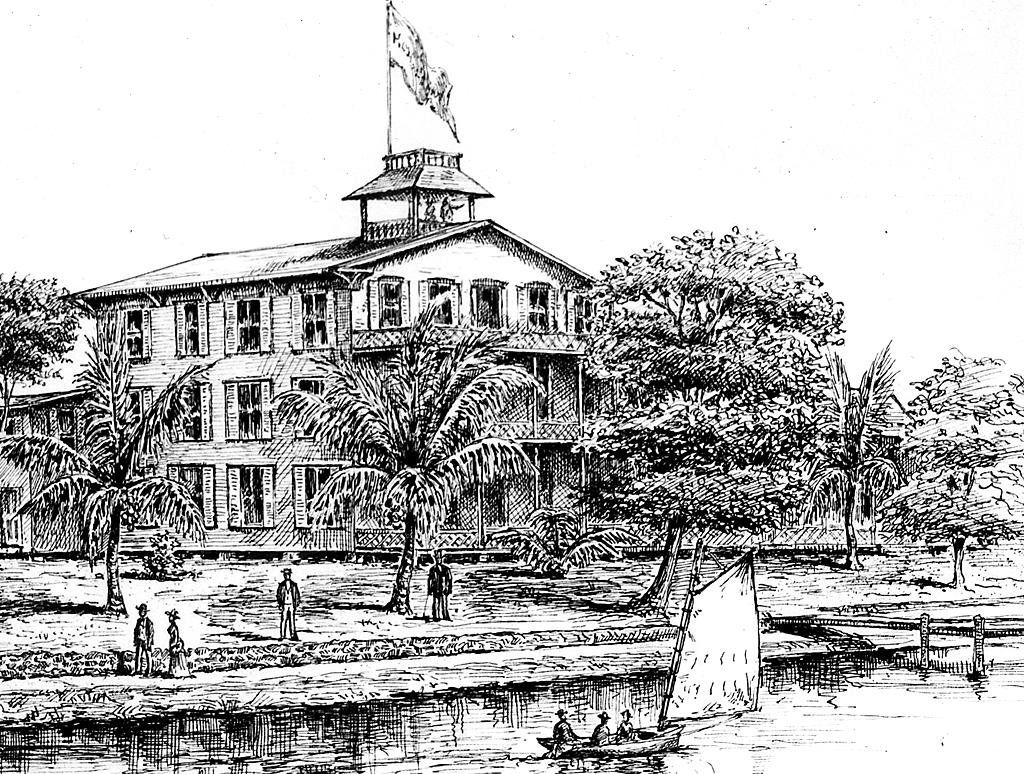

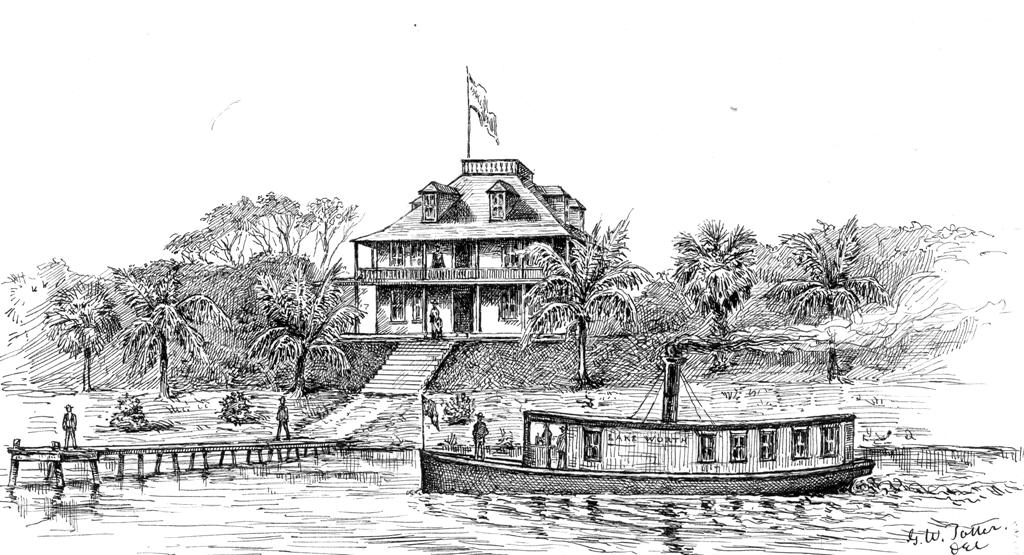

Much like Elisha Dimick, owner of the Cocoanut Grove House, Dye saw an opportunity to provide for tourists and settlers. In the early 1880s, after Dye had placed the Gazelle into service, he began selling groceries from his homestead. According to pioneer Charles Pierce, Dye’s store was an “appreciated establishment,” because the settlers no longer had to travel to Titusville or Jacksonville for the basic “necessities of life.” In 1886 he opened a ten-room hotel with a grocery store in the area of today’s Palm Beach Country Club. Two years later, tourists were so numerous, Dye constructed the sixty-three room Hotel Lake Worth, the largest hotel in the area until the Hotel Royal Poinciana opened in 1894. This was the first structure to be designed and built as a hotel in the lake area. There were also two cottages, one on each side of the main building. In July 1888, lumber for the hotel was transported by boat from Jacksonville. By October, Dye was putting the finishing touches on the hotel to open for the winter season.

Situated on high ground, the hotel property extended from lake to ocean and had a large truck garden to supply guests with fresh vegetables. For eleven years Dye hunted every Saturday to provide fresh meat for his family and visitors. In his memoirs, Dye wrote he did not ever have to buy meat. Traveler William Drysdale of New York described the hotel as the “best hotel in this part of Florida, a large house heated with steam.” By the 1891-1892 season, Dye had opened the Lake Worth Laundry Service, which may have been located on the hotel grounds.

In 1892 Dye had an unscheduled guest after the hotel had closed for the season. On April 14, James E. Ingraham, who at the time was president of South Florida Railroad Company, owned by Henry Plant, arrived at the hotel. But in the near future Ingraham would be working for Henry Flagler. Ingraham was on a two-month exploration of south Florida through the Everglades from Fort Myers to Miami, then north along the east coast. His journey began in March 1892, and he arrived on Lake Worth the middle of the following month. When Ingraham arrived, his party attempted to make it to the Cocoanut Grove House. However, inclement weather prevented them from reaching it though they were able to make it to Dye’s hotel. Ingraham spent the night and departed for Jupiter the following day. Even though he was only here for a night, Ingraham had mixed feelings about Lake Worth. In his diary he wrote, “Lake Worth impresses me very favorably by reason of handsome improvements but does not compare with Biscayne Bay, in my opinion, for fruit or residence; don’t like the dirty lake water.”

The hoteliers of Lake Worth had many visitors to provide for. The 1893 season was a very busy time for Dye. His busiest months for that year were February and March with 670 guests. From January 1890 to January 1895, when the Hotel Lake Worth register (the only extant copy) ends, 2,859 people stayed at Dye’s hotel. For some unknown reason, children staying at the Hotel Lake Worth were registered as one-half a person.

The well-known hotel fell victim to fire early Sunday morning, July 18, 1897. The Dye family was sleeping when fire erupted in the east wing of the hotel. A bright light disturbed Dye’s daughter Ruby. She looked out a window to see the kitchen area engulfed in flames and quickly woke her mother and father. Running outside with a firearm, Dye fired into the air to bring help.

Neighbors in the area reached the scene to help save what they could from the burning structure. They also helped by throwing water on a cottage to the south to keep it from burning. Despite everyone’s best efforts, the inferno completely consumed the hotel. According to Dye, the loss of the building cost him about $12,000. During the fire, ammunition Dye stored in the hotel exploded, causing some excitement, as people had to seek cover behind trees and surrounding buildings.

Dye never rebuilt the hotel and finally sold the property in 1913. He did go on to work in dairy farming, land development, and auto sales. When Dye established his dairy farm, he brought the first dairy cows to the Lake Worth area. During the Spanish-American War, Dye received a military contract to open a dairy farm in Cuba to supply U.S. troops with milk. He later sold his dairy farm to the East Coast Hotel Company, which built a golf course on it. Dye was married twice and raised four children. He is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in West Palm Beach.

“Clever genial people make [the hotel] just what it is–a pleasant home place for rest and ease.”

-Anonymous, ca. 1890s

Oak Lawn House

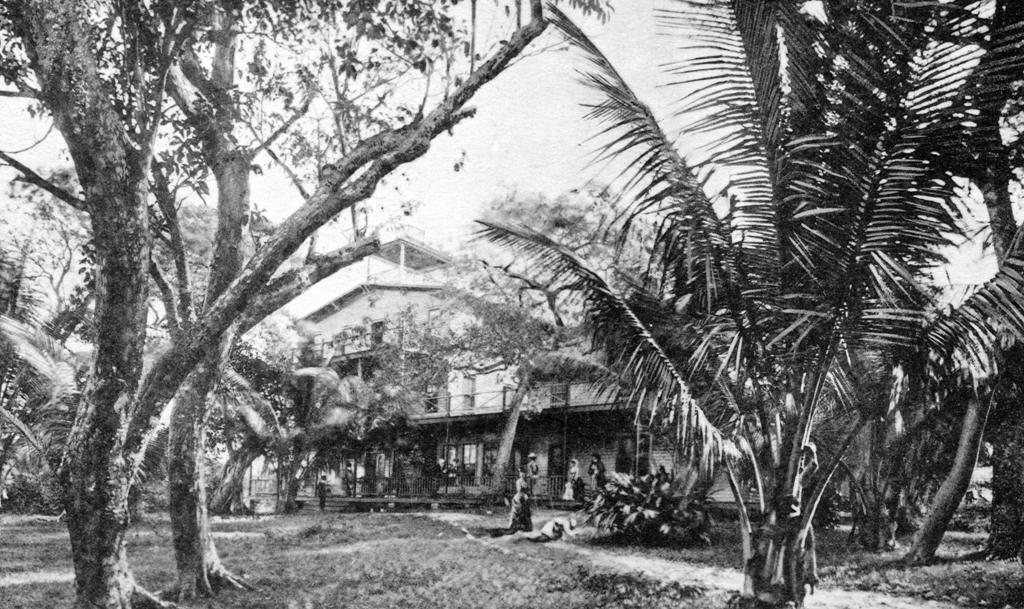

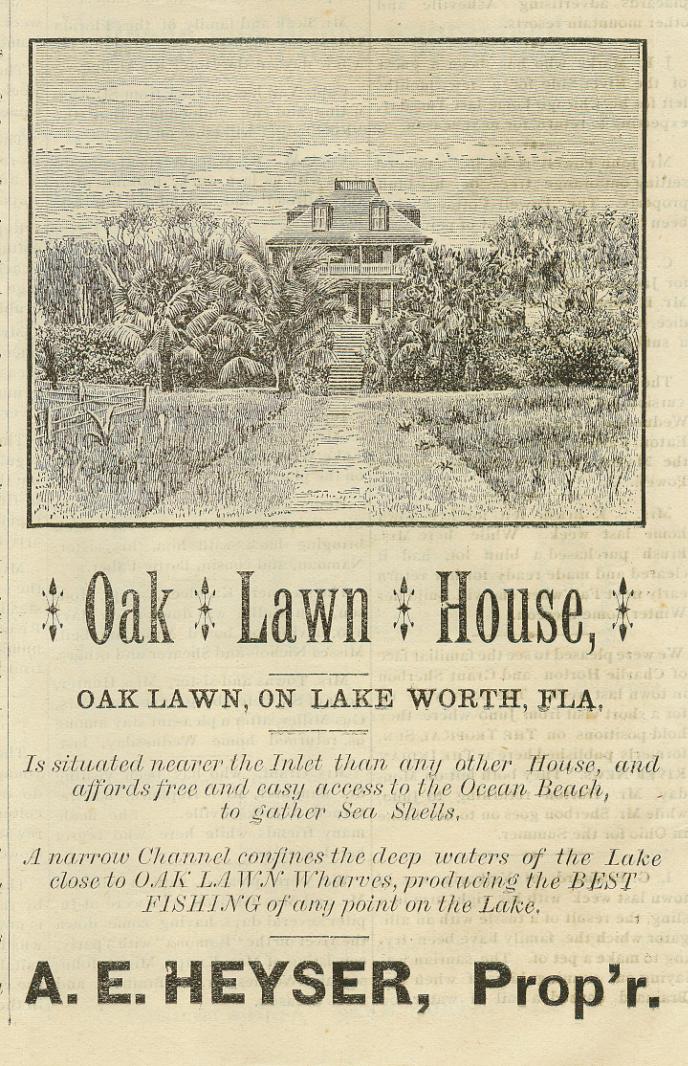

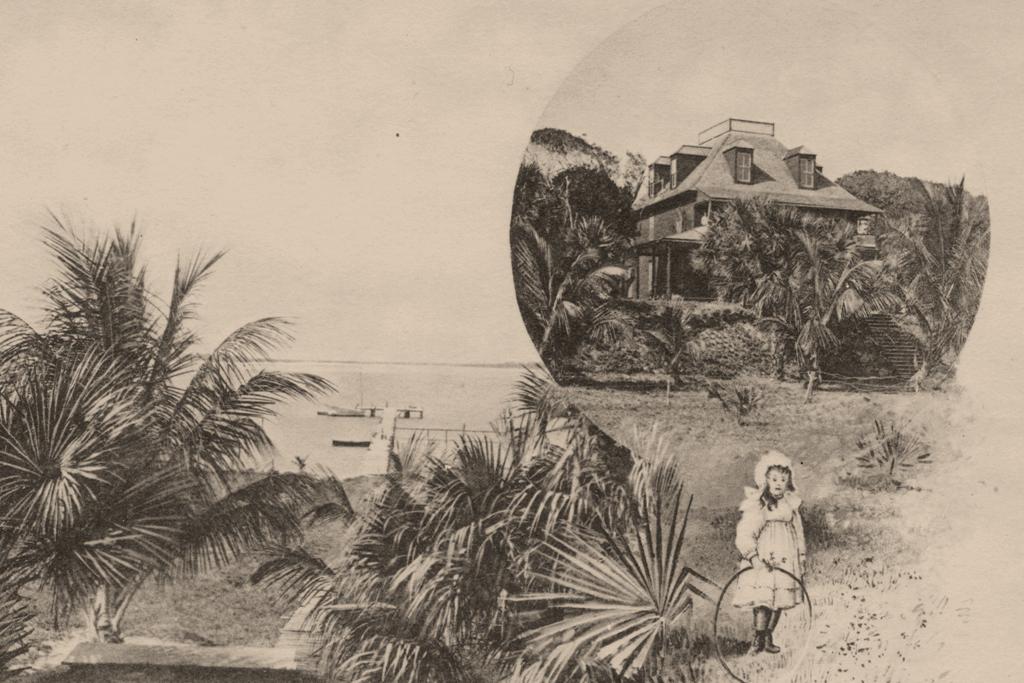

The Oak Lawn House was another Pioneer Era hotel on Lake Worth. It was located on lakefront property in the area of what is now 10th to 12th Street in Riviera Beach. In 1882 pioneer Allen E. Heyser (1857-1924), who would later become an attorney and Dade County judge, settled on eighty acres therefore becoming the first resident of what became Riviera Beach. He purchased the land for $500 from Frank Dimick, who bought it in 1881 but never settled there. Six years later, Heyser married Mattie Spencer, daughter of Valorus O. Spencer, the postmaster of the Lake Worth post office. The couple first built a small house but kept building until they completed a three- story, twenty-room structure they named Oak Lawn House. The name Oak Lawn was taken from five huge oak trees on Heyser’s property. The hotel sat on a high bluff, said to have been thirty feet high, which was an ancient Indian shell mound. It ran down to the lakeshore with an embankment that extended three- quarters of a mile along the shore. This location gave the hotel a commanding view of the surrounding countryside and lake.

On August 16, 1888, a hurricane struck the region causing some damage to Oak Lawn House, which was still under construction, and completely destroying the hotel dock. Despite minor damage to the building, by the end of August, Heyser was able to move in. By October, all that was needed was furniture for the hotel to be ready for the winter season. When it opened, Heyser offered guests single rooms or suites.

Between November and December 1888, as Heyser prepared to open the hotel for the winter season, he applied to the Postmaster General in Washington, D.C., to establish a post office named “Oak Lawn.” In February 1889, he received approval for the post office located at his hotel. It opened on 13 February, with Mattie Spencer Heyser as postmistress. This was the fifth post office to open in the lake region. Renting a room at Oak Lawn in 1892 cost a visitor $2.00 to $2.50 a day or $10.00 to $12.00 a week for room and board.

By 1893, the hotel owners had added a telegraph office at the hotel. During one particularly busy season, according to Mrs. Heyser, the hotel was nicknamed “Syracuse House because most of the guests were from Syracuse, New York.”

A few years later, The Tropical Sun provided its readers with a description of the Oak Lawn House property. The unknown writer stated it was a “well-appointed establishment, a fine garden, a profusion of dairy products, fine fruit trees, well-kept premises, clever genial people make it just what it is – a pleasant home place for rest and ease.” Mattie Heyser grew a variety of vegetables such as potatoes, beans, beets, tomatoes, cabbage, and strawberries. In February 1892, winter visitor Emma Gilpin wrote about her short stay at Oak Lawn before moving to the Cocoanut Grove House on Palm Beach. She said that the rooms were comfortable, but the food was rather poor. She and her family were regulars at the Cocoanut Grove House.

In 1893, a visiting journalist staying at the hotel remarked that the area was “the Riviera of America.” Heyser liked the name Riviera and applied to the U.S. Postal Service to have the name of the post office changed to Riviera, which was approved in April 1893. That same year, Heyser hired a manager to oversee the daily operations of the hotel. Dr. E. Hinckson is listed as the proprietor on an advertisement in The Tropical Sun in April 1893. Like the Cocoanut Grove House, entertainment was held at Oak Lawn. One such event was a musical performance reported by The Tropical Sun in September 1891.

Heyser, who had been elected as a judge in Dade County, moved to Miami in 1899 when the county seat was relocated from Juno back to Miami. Juno was located at the north end of Lake Worth and was the seat of Dade County 1889-1899.

In 1900, Heyser exchanged properties with Dr. Ashton H. Cary, a Georgia physician. Heyser received full ownership of a piece of property held jointly in the name of both men. In return, Cary got the hotel property. After the transaction, Cary put the hotel up for sale. Sometime in 1901 or 1902, Iowa entrepreneur-inventor Charles Nelson Newcomb purchased Oak Lawn Hotel for $2,500. By this time the hotel had been closed and had fallen into disrepair.

Newcomb was born in New York in 1850. As a child he did carpentry work with his father, and as a teenager he left home to join an uncle in Illinois where he worked in carpentry. After making a small fortune, Newcomb moved to Iowa where he began manufacturing wagons in Lewis. While living there, Newcomb invented a textile machine called the Flying Shuttle Rag Carpet Loom and moved into the loom business where he made his larger fortune. He later invented and received a patent for the Fly Machine (a type of textile machine) and the suction dredge in 1905. The dredge was later used to dredge the lakeshore in front of Newcomb’s property.

Newcomb was already familiar with the Oak Lawn property. During vacations to Palm Beach in the 1890s, he and his family would sail from Palm Beach to Oak Lawn to have tea at the hotel. After he bought the property, Newcomb converted the hotel into his family residence. According to Edith Newcomb, her father did not like the name Oak Lawn; he preferred the name “Riviera” and spelled “Riviera” out in bleached conch shells placed in the front yard facing the lake. During renovations to the structure, Newcomb extended the porch and added an enclosed observatory to the top of the house.

During the renovation, he planted several varieties of fruit trees on the old hotel property. In 1914 Newcomb investigated the Indian mound, upon which the hotel-turned-residence sat, sending his findings and a detailed map to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where the findings are now on file at the Museum of Natural History. Prior to Newcomb’s investigation, Heyser and his father had examined the mound. They had found evidence of human and animal bones and iron artifacts. The mound stretched across the lakefront, between 11th and 12th streets, to the west side of Avenue E.

Newcomb owned the old hotel until 1919, when he sold the property to local developer Thomas J. Campbell for $30,000. At the time of the sale, The Palm Beach Post reported the property had a park in front and 350 feet of lakefront that extended 230 feet west, and a house with twenty-one rooms. Campbell planned to change the structure from a residence to a clubhouse, to entertain various groups of “yachtsmen and fishing parties.” The following year the Heyser/Newcomb place was advertised as the Hotel Riviera Café managed by R.A. Dewees. Following this, the property changed hands several more times.

Charles Newcomb was ambitious and set out to develop Riviera as a resort like Palm Beach. He had the area surveyed and marketed for sale. In 1922 the Town of Riviera was incorporated and Newcomb was appointed town clerk. By the 1930s, Newcomb had passed into obscurity and both the hotel and Indian mound were demolished. The Port of Palm Beach now occupies some of the area where the last pioneer hotel once stood.

Odds and Ends

Visitors arriving in the Palm Beach area during the Pioneer Era were an adventurous lot. They came to enjoy the wilderness paradise of south Florida and to participate in the various sports offered, such as fishing, hunting, and boating, that continue today. Fishing was excellent on the lake or the ocean. As for hunting, the island jungle and the mainland were teeming with wildlife. By the early 1900s, most of the wild animals had moved further inland to escape the growing human population or had been killed off.

Another aspect of the pioneer hotels’ appeal was their location on the shores of Lake Worth, not the ocean. As the highway of the day, the lake provided the greatest ease of transporting goods and people. All hotels had docks where boats could drop off visitors at their front doors. An underlying reason for the hotels’ locations on the lake may also have been more shelter on the lakeside from storms coming from the east.

Services at the early hotels would have been limited. At least in the beginning, the owners’ wives more than likely were the cooks preparing the daily meals for both family and guests. They would also have provided a limited maid service. One guest, Josephine Davidson of New York, found out the hard way about the limited services when she and her husband, James Wood Davidson, stayed at the Cocoanut Grove House in 1884. She had to cook and wash for the both of them, which she had to learn very quickly to do since Josephine was unaccustomed to these chores. A year after arriving in Palm Beach, James and Josephine built their home “Osera” on the west shore of Lake Worth. By 1891, Dye may have employed at least one bellboy, a young African American who was a “hall boy” at the Royal Victoria Hotel in Nassau. Traveler William Drysdale recognized the boy when he came down to the Hotel Lake Worth’s boat dock to pick up Drysdale’s bag.

By 1891, the Hotel Lake Worth offered laundry services as noted by laundry charges in the guest register. Some wealthier clients traveled with servants, who took care of their employers’ daily needs. These servants can be found in the registers, most only listed as maid, nurse, or servant. For instance, Julia Tuttle’s maid is registered as part of the Tuttle party in November 1891 not by name but only as “maid” at the Cocoanut Grove House. Pittsburgh millionaire and later owner of the Cocoanut Grove House, Charles J. Clarke registered his servants at Dimick’s as “maid and man servant.” On September 26, 1886, W.H. Benedict of New Brunswick, New Jersey, and his family stayed at the Cocoanut Grove House. They registered their servant as “Colored Servant.” Since the register is not clear as to what room the servant was given, it is unknown, given the era, where a colored servant would have stayed during the visit.

For the visitors, there was plenty to keep them busy in the lake area during their winter visits. According to John and Emma Gilpin, who were regular guests at the Cocoanut Grove House, the 11:00 am “sea bathing” was a daily ritual. Sewing bees for the ladies were common and held at various houses of locals or seasonal residents. Some guests at the Cocoanut Grove House engaged in the game Blind Man’s Bluff during the evenings in the parlor. Boating was a favorite activity both during the daytime and at night by moon- light. They often called at different houses to visit the locals and to have lunch or dinner. There were picnic excursions to the inlet, islands, or the mainland.

Visitors also went hunting on the mainland for ducks, birds, bear, and alligators. Fishing was a favorite pastime for both guests and locals who fished from boats, docks, and the beach. Guests went to church at the Episcopal Church of Bethesda-by-the-Sea and various get-togethers held there. There were plenty of activities to occupy one’s time as indicated by letters sent home to friends and family.

The opening of Henry Flagler’s Royal Poinciana Hotel and the passing of the Cocoanut Grove House signaled the end of the Pioneer Era though Oak Lawn House and Hotel Lake Worth continued to operate until one burned down and the other was sold and converted into a private residence. Regardless of their demise, they were important to the development and economy of the area. The hotels provided monetary support for the owners and their families. In turn, others earned cash by providing transport services and supplies to the hotels and their guests.

The pioneer hotels are, for the most part, forgotten and overshadowed by the memory of the Royal Poinciana Hotel and by Flagler’s other hotel, The Breakers, which is still operating. The first hotels may not have been as grand and magnificent as their larger counterparts built by Flagler but the rustic environment, mild climate, and the great hospitality of the owner-operators appealed to many northern visitors. The early hotels were the beginning of tourism and the service industry in a semi-tropical jungle that was soon transformed into a world-class resort.

Selected References

Books

Bradley, Alford G. and E. Story Hallock. A Chronology of Florida Post Offices Handbook 2.The Florida Federation of Stamp Clubs, 1962.

Brink, Lynn, ed. A History of Riviera Beach, Florida. The Bicentennial Commission of Riviera Beach, Florida, 1974.

Curl, Donald W. Palm Beach County: An Illustrated History. Northbridge: Windsor Publications, 1986.

Foster, Charles C. Conchtown, USA. Boca Raton: Florida Atlantic University Press, 1991.

Gardener, C.M. and C.F. Kennedy, Business Directory, Guide and History of Dade County, Florida for 1896-97. West Palm Beach, 1896.

Linehan, Mary Collar and Marjorie Watts Nelson. Pioneer Days on the Shores of Lake Worth 1873-1893.St. Petersburg: Southern Heritage Press, 1994.

Norton, Charles Ledyard. A Handbook of Florida, 3rd ed. revised. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1892.

Norton, Charles Ledyard. A Handbook of Florida, 3rd ed. revised. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1892.

Pierce, Charles W. Pioneer Life in Southeast Florida. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1990.

Robinson, Tim. A Tropical Frontier. Port Salerno, FL: Port Sun Publishing, 2005.

The Book of Florida.The Florida Editors Association, 1925.

Travers, J. Wadsworth. History of Beautiful Palm Beach.West Palm Beach: Palm Beach Press, 1928.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County Files

Gilpin, Emma. Letter Sunday, February 21, 1892.

Unpublished manuscript by Mrs. John [Emma] Gilpin, Gilpin Family Collection, HSPBC.

Dye, H.P. Mrs. Dimick’sScrapbook. Dye File, HSPBC.

Dye, H.P. Memoirs of His Life in Palm Beach County, 1929. Addressed to Helen, Margaret, and H.P. Dye Jr. Dye File, HSPBC.

Hotel Lake Worth Guest Registry, 1891-1895. Archives Collection, HSPBC.

Rowley, George S. “History of Old Lake Worth from Local and Personal Interviews of Old Resident,” newspaper clipping, January 20, 1924, vertical files, HSPBC.

Peebles, J.D. “The First Judge, and the First Postmaster in Palm Beach County.” Oral Interview [typed transcript] with Mrs. Allen E. Heyser, January 8, 1936.

Newcomb, Edith L., typed diary. Newcomb file, HSPBC.

Articles

“Advertisement,” Florida Star, December 27, 1888, Microfilm Collection, Central Brevard Public Library, Cocoa, FL.

“Captain Dye is Dead Here in 79thYear,” Palm Beach Times, December 1, 1930.

Davidson, Josephine. “A Reminiscence,” The Lake Worth Historian(1896), 14.

Drysdale, William. “Journey to Lake Worth,” The New York Times, February 23, 1891.

“First Settler on Lake was Confederate Draft Dodger by Name of Lang,” Tropical Sun, February 26, 1937.

“Hotel Lake Worth Burned,” Tropical Sun, July 22, 1897.

Keys, Emilie C. “Storm Scares? There were none in Florida’s 1881-1914 Era,” Palm Beach Post-Times, November 21, 1948.

“Lake Worth,” Florida Star, August 7, 1888, August 30, 1888, October 11, 1888, December 13, 1888, February 28, 1889, Microfilm Collection, Central Brevard Public Library, Coca, FL.

“Lake Worth a general write up of all points of interest,” The Tropical Sun, September 19, 1891.

Marchman, Watt P. “The Ingraham Everglades Exploring Expedition, 1892,” Tequesta, 1947, 3-43.

“Newcomb Restores the Old Hotel into a 22 Room Mansion,” Palm Beach Post, July 6, 1972.

“Purchase of Armory by Capt. H.P. Dye being Negotiated,” Palm Beach Post, September 24, 1919.

“Riviera Hotel Property Sold to T.J. Campbell for $30,000,” Palm Beach Post, July 11, 1919.

“Thomas Purchases Half Interest in Hotel at Riviera,” Palm Beach Post-Times, March 28, 1924.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County

You might also enjoy

A Celebration of Pride

A Celebration of Pride A Place for Pride | 50

A Portrait of Leadership | 2024

A Portrait of Leadership | Panel Discussion Women’s History Initiative,

The Evolution of Resort Wear

From the iconic prints of Lilly Pulitzer to the timeless elegance of Palm Beach’s historic hotels, Behind the Palms shares the legacy of resort wear and how Palm Beach’s influence on fashion remains strong.

LOVE, LOVE FLORIDA HISTORY ESPECIALLY PALM BEACH COUNTY. I WAS BORN & RAISED IN PAHOKEE FL 1942 AND WE OFTEN CAME TO WPB FOR SCHOOL SHOPPING AND ENTERTAINMENT. MY GRANDFATHER WAS ONE OF THE FIRST COUNTY COMMISSIONERS IN OKEECHOBEE FL. EDDIE O UPTHEGROVE. COMMERCIAL FISHERMAN WITH HIS BROTHER ON LK. OKEECHOBEE.

Fascinating. The ingenuity, foresight and work ethics needed to produced such wonderful places of respite and adventure seem lost to us today. What I found of most interest is the reference to “Indian mounds” as placements for the hotels and that Newcomb alerted the Smithsonian to his discoveries. But what, if any, was the Smithsonian’s reaction to this evidence? I’m curious as to the indigenous tribe [perhaps, one of the Seminole tribes?] that may have established these “Indian mounds”.

Thank you for your comment, Mary. If you wish to use our research services, please email Director of Research Rose Guerrero at rguerrero@pbchistory.org or visit https://pbchistory.org/research-room/. Take care.