By Christian Davenport

This article is reprinted from the Spring 2012 issue of Tustenegee. For proper context, please note the original publication year of all reprinted articles here, which receive only minimal editing.

I love the Glades! I love the land, the people, the pace of time, the food, and the culture. Each community has its own identity, feel, way, and history. Sure, the area has its problems, but even with its problems, all of the Glades people share a pride and a connection to the land that is more often associated with the “fly over states” than with Palm Beach County. This is because the entire area’s focus is on agriculture, and historically the entire Glades region represents America’s last frontier. One must remember America’s “Wild West” was long-settled when the towns in the Everglades were just being conceived. As a result of the combination of these facts, the people of the Glades are very attuned to the environment and don’t quit trying to improve their way of life.

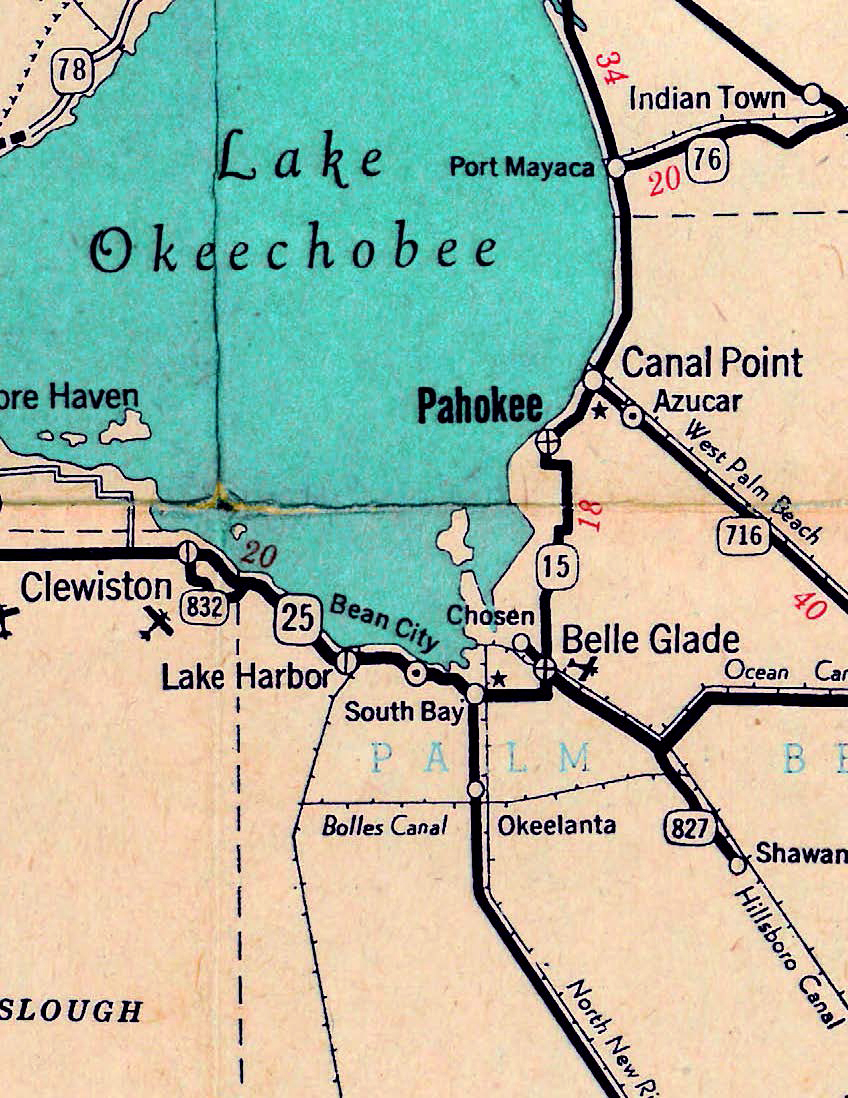

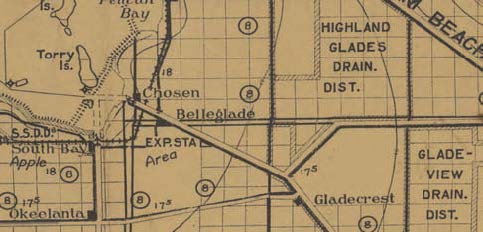

Have you ever wondered where the term “the Glades” came from? It doesn’t appear on maps. Which communities are included in the area depends on whom you ask and from where that person came. For example, people on the coasts will not always include Moorehaven or Clewiston in the “Glades” communities. Yet most people in the western communities would include them. In short, the term refers to a collection of communities that are located in the area of the former Everglades concentrated around Lake Okeechobee. Historically, these communities were referred to collectively as the “Everglades Towns” or “those towns in the Everglades.” These names were shortened to “the Glades” sometime in the late 1940s. However, in the earliest part of the 20th century you were more likely to hear the term “Sawgrass Towns” when referring to the western communities. The earliest developments were Okeelanta and Glades Crest/ Gladescrest. These two towns were surveyed, platted, and literally cut out of the sawgrass marshes south of Lake Okeechobee.

To understand the Everglades–all of the Everglades–one must accept the fact that the area is a mosaic of diverse and dynamic ecotones that are greatly affected by environmental conditions. This diversity is not a recent phenomenon. When the area is viewed in a geological time frame, the area that encompasses today’s Everglades has been everything from ocean floor to a shoreline, to a massive grassy plain, to a swamp, to today’s mixture of farmland and wetlands. Humans have likely occupied the Everglades for the last 12,000 years. Starting in the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), the area was a mosaic of pine flatwoods and grasslands. Paleontologically, it is known that during this time the area was home to mammoths, mastodons, horses, bison, and deer. Then, during the Holocene (about 8,000 years ago), the area slowly changed from the grassy plain into the “drowned” grassy quagmire the early explorers named the Everglades. One fact is a constant: as long as humans have lived in the area, they have tried to change it to suit their needs.

The communities in the northern Everglades were founded and developed under the paradigm of manifest destiny. Under this doctrine, the population had a duty to expand and, when required, bend nature to its will. Case in point: the swamps, sloughs, and lakes of the Everglades needed to be controlled to benefit humanity. What becomes clear is that the history of the Glades area is so intertwined with its environment that one cannot be understood without taking into account the other. Simply put, the history of the northern Everglades, including Lake Okeechobee, is punctuated by economic boom and bust cycles that are the result of early settlers impacting the ecology of the area.

Several major economic booms have occurred in the northern Everglades region. These are the efforts in draining Lake Okeechobee, commercial hunting and fishing, and commercial agriculture. These boom periods were followed by five ecological busts. These were the draining of Lake Okeechobee and surrounding landscape, the introduction of water hyacinths, the over exploitation of various animal species, the deforestation and removal of native vegetation, and the canalizing of the surrounding lands culminating with the impoundment of Lake Okeechobee.

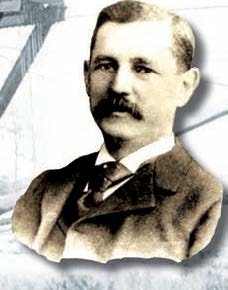

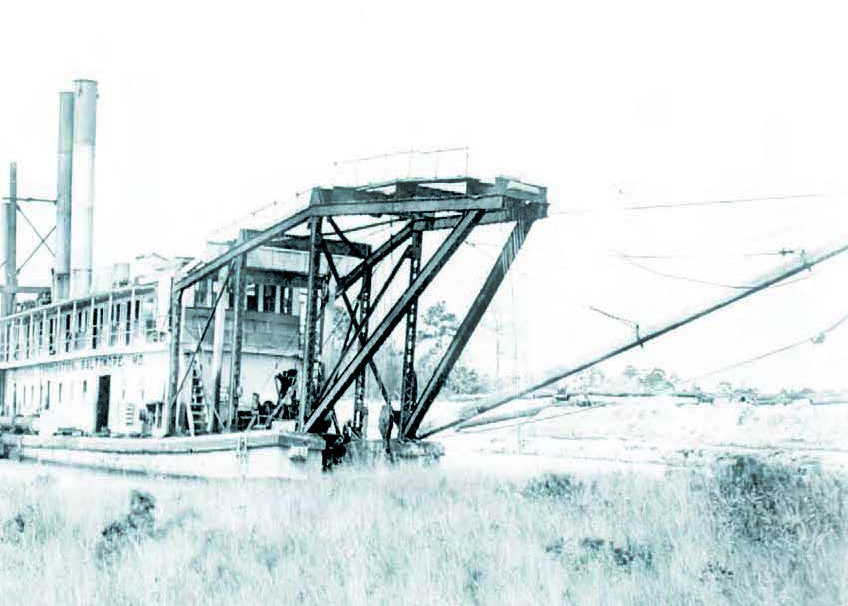

The initial economic boom for the northern Everglades occurred during the 1890s with [developer] Hamilton Disston’s plans to drain the “excess” water from the area. The focus of this effort was centered on Lake Okeechobee. Disston and his partners poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into all sectors of the region’s blossoming economies. They canalized rivers, removed timber, promoted land sales (their lands), and as a result the railroad barons of the day brought rail lines into the region. In the end, what Disston accomplished was lowering Lake Okeechobee by four feet and losing millions. Lowering Lake Okeechobee was the first major ecological change directly attributable to the actions of humans in the Everglades. No solid scientific data exists to show exactly how this affected the area but there was clearly habitat loss for aquatic animals and plants which in turn led to the expansion of grasses.

The second economic boom came in the form of professional hunters. These hardened souls were the first non-native American peoples to inhabit the Everglades during the historic period. Hunting was unregulated and as a result, as one species became endangered and, in the worst case, extinct, a replacement was found. This is best exemplified by river otters and raccoons. River otter pelts brought the greatest amount of money but when they became scarce, raccoon pelts increased in value. Plume hunters (bird hunters) in the region earned the most money of all the commercial hunter types, supplying the demand for stuffed dead birds and bird feathers to adorn women’s hats. The removal of these species greatly impacted the environment. Once the predators like otters, raccoons, egrets, and herons were removed from the environment, prey species, primarily fish, dramatically increased. This helped to create the third economic boom.

Commercial catfishing on Lake Okeechobee began around 1900 and became the most profitable of the early economic industries in the northern Everglades. A record 6,500,000 pounds of catfish were removed from the lake in 1924. Millions of dollars were made annually shipping catfish out of the lake for approximately thirty years. The eventual collapse of this industry was the result of the third ecological impact. The next impact was the result of a combination of factors including the introduction of large seine nets which allowed tons of fish to be caught in a single haul and the diking of the southern end of Lake Okeechobee.

In 1925 farmers demanded an earthen dike be constructed around the southern end of the lake to protect their crops from periods of high water. This was constructed of local muck soils and was crudely made. While it leaked badly, it worked well enough to cut off the flow of water to the rivers that existed around the lake. These very rivers served as the breeding grounds and nurseries for many fish species. A lack of breeding grounds combined with overfishing led to an economic bust but set the stage for the next economic boom.

With the land “drained,” or at least draining, agricultural efforts were taking off, including cattle ranching. Cattleman Eli Morgan brought water hyacinths from the St. Johns River area to the canals throughout the northern Everglades. His thinking was that these plants would be a food source for the blossoming cattle industry in the region. These plants, while small in size, multiplied quickly and brought all barge and boat travel through the Everglades to a stop. Historic photographs show people standing on the surface of canals being supported by the hyacinths. Until a means of controlling these plants was found, they had a major economic impact on both the interior and coastal communities.

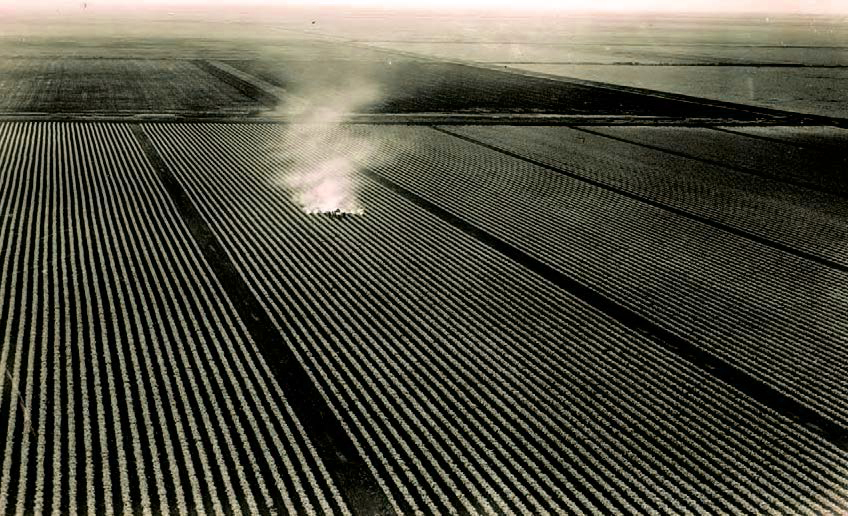

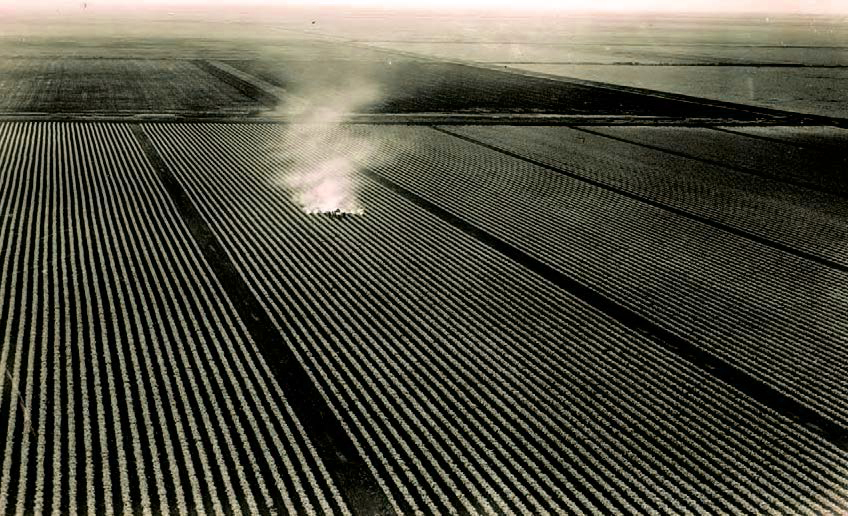

Around 1905-1928 the entire Glades region was promoted worldwide as the last frontier with the newest, cheapest, and most profitable farmland ever discovered. It became clear farming was set to far surpass any of the profits made by all the previous economic undertakings combined. During this time two ecological impacts were occurring simultaneously; these were the successful draining of the “excess” water followed by the clearing of the land. With the main drainage canals and thousands of lateral canals excavated, the water could be “controlled.” With the land dry the pond apple forest and the extensive sawgrass plains on the eastern and southern sides of Lake Okeechobee were removed. These two processes resulted in the muck soils desiccating, subsiding, and burning, earning the area the name “the land of a thousand smokes.”

The last ecological impact occurred following the thousands of deaths during the 1926 and 1928 hurricanes. After these storms, the federal government constructed the Herbert Hoover Dike, the last hurdle in overcoming the Everglades. While the dike contained the source of the waters for the Everglades, it had an unexpected effect in that it isolated the lake from its natural and cultural surroundings. The early pioneers learned the hard way to fear the power of the lake but used the lake and its canals to transport goods to the rest of the world. As the lake was cut off and canals were blocked, towns began to shrink and eventually fail as a result of isolation.

Looking to the future, two more ecological impacts await the former northern Everglades. The first is the depletion of muck soils and the second is large-scale mining. The fact is that the muck soils which have been the economic engines of most of south Florida will eventually become depleted. Land owners in the Glades area are looking for a means to keep their land profitable. To this end, several large-scale rock mines (3,000 acres and up) are planned for the Glades area. Current thinking is the depleted mines can be used to hold excess water from Lake Okeechobee.

However, such a gesture is sophomoric at best; after all, how will holding water turn a profit? An alternative idea is to use the former mines to grow exotic algae for use in the production of bio-fuel. Given Florida’s problems with the accidental release of exotic life forms, the risks associated with this latter idea must be carefully evaluated. For example, in 1949 a hurricane dropped unprecedented amounts of rain causing canals in the region to overflow. So much water fell, a sheet flow of water covered the entire region. What would result if a similar scenario released an exotic algae throughout the Everglades and its interconnected canals?

Although cliché, the axiom holds true. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat past mistakes. Nowhere has this lesson been more overlooked more often than by “outsiders” trying to turn a profit in the Everglades. In light of the facts presented when examining the history and the future of the Glades area, it becomes necessary to ask, “Did manifest destiny shape the Everglades or did Evergladesdestiny shape the past, present, and future of this amazing region?”

About the Author:

Christian Davenport serves as the Palm Beach County Archaeologist and Historic Preservation Officer for Palm Beach County. He has lived in Palm Beach County since 2005. Davenport was the lead archaeologist investigating/recording 33 new archaeological sites in Lake Okeechobee during the 2007-2009 drought. In 2010-2011, he excavated sand and shell mounds at DuBois Park in Jupiter. At the time of writing this article, Davenport was researching the large ancient Indian earth mounds around Lake Okeechobee, which resulted in a 800-plus page report on the excavations at Lake Okeechobee.

Selected References

Information for this article was gathered from:

The archives of the Lawrence E. Will Museum, Belle Glade, Florida.

Will, Lawrence, E. A. Cracker History of Okeechobee. West Palm Beach: Sir Speedy, 2002, fifth printing.

______________. Swamp to Sugar Bowl: Pioneer Days in Belle Glade. Belle Glade: The Glades Historical Society, 1984, second printing.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County

You might also enjoy

Wish You Were Here: Tourism in the Palm Beaches

Wish You Were Here: Tourism in the Palm Beaches November

A Celebration of Pride

A Celebration of Pride A Place for Pride | 50

A Portrait of Leadership | 2024

A Portrait of Leadership | Panel Discussion Women’s History Initiative,