Statehood to the Civil War

Click below for a downloadable copy of this article.

STATEHOOD

The Florida Constitution was written in 1838, one of the steps required to become a state. After the Second Seminole War ended, more settlers came to Florida, bringing the territory’s population to 57,000 people, but still not 60,000, which was needed for statehood.

At the time, the U.S. Congress would admit states only in twos: one slave state and one non-slave state, to keep a balance in the number of congressional representatives. Since Florida was a slave-holding territory, the U.S. Congress would not allow it to become a state until a non-slave territory was also ready to become a state. On March 3, 1845, Florida was finally admitted to the Union as the twenty-seventh state, and Iowa was admitted as a non-slave state.

THE CIVIL WAR

By 1850 the population of Florida had grown to 87,445 people, including about 39,000 slaves and 1,000 free Blacks. Differences over slavery between the North and South had been going on for decades. Agriculture dominated the southern economy, where slaves were depended upon to work the fields. The North focused on industries such as manufacturing, which did not depend on slaves.

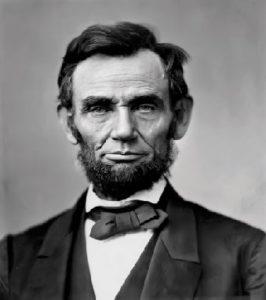

When Abraham Lincoln was elected U.S. president in 1860, the southern states worried that the new government would end slavery, destroying their economy and society. South Carolina was so angry about the outcome of the election that it seceded from the Union in December 1860, separating from the other states under the U.S. government. Less than a month later, Florida became the third state to secede (after Mississippi). Additional states seceded, forming the Confederate States of America. The American Civil War began in April 1861, when South Carolina troops fired on federal forces at Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor.

An estimated 16,000 Floridians fought in the war. Most were in the Confederacy, but about 2,000 joined the Union army. Nearly 5,000 Florida soldiers lost their lives during the war.

While most of the men in Florida were away fighting in the war, the women, children, and slaves kept the farms and plantations working. They raised crops and cattle to feed Confederate troops. They also sent them pork, fish, fruit, and salt. Florida was the largest producer of salt, which was important to keep meat from spoiling. Salt was separated from seawater at salt factories in coastal areas.

Florida was also an important producer of cattle. Confederate agents ordered thousands of cattle to feed southern troops. For part of the year, cattle were driven north into Georgia and the Carolinas. During the fall and winter seasons, however, there was no grass for the cattle to eat in those states. They were taken instead to Florida, where the climate was mild and grass grew year-round. Thousands of cattle were raised and slaughtered in Florida, salted to avoid spoilage, packaged, and shipped to the Confederate army.

Most of the war was fought outside of Florida. The battles that occurred in the state were Santa Rosa Island in 1861; Olustee, 1864; Marianna, 1864; Gainesville, 1864; and Natural Bridge, 1865. Tallahassee was the only Confederate capital east of the Mississippi River that was not captured by Union forces.

THE JUPITER INLET LIGHTHOUSE

A lighthouse is an important navigational aid located at either a prominent land feature or a dangerous place for navigation. It warns ships of perilous reefs or coasts and guides them into a safe harbor or back out to sea. Many lighthouses were built along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, the oldest structure in Palm Beach County, stands at the entrance to Jupiter Inlet, where the Loxahatchee River, Indian River, and Atlantic Ocean meet. Loxahatchee is a Seminole word meaning turtle river.

The U.S. Congress approved building the lighthouse at Jupiter to help prevent shipwrecks in 1853, but it was delayed until 1860 because of the Seminole wars. The lighthouse is 156 feet above sea level. The tower is 108 feet high and sits on a 48-foot, ancient high dune, and has 105 steps. The tower is eight bricks thick, or 31.5 inches, at the base and tapers to three bricks thick, or eighteen inches, at the top. The beam of light is 146 feet (focal beam) and can be seen up to twenty-four miles out at sea. Today the lighthouse is still a navigational aid to mariners and is open to the public for tours.

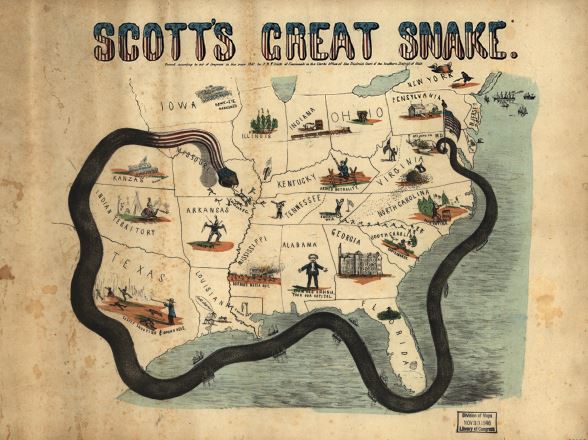

CONFEDERATE BLOCKADE RUNNERS

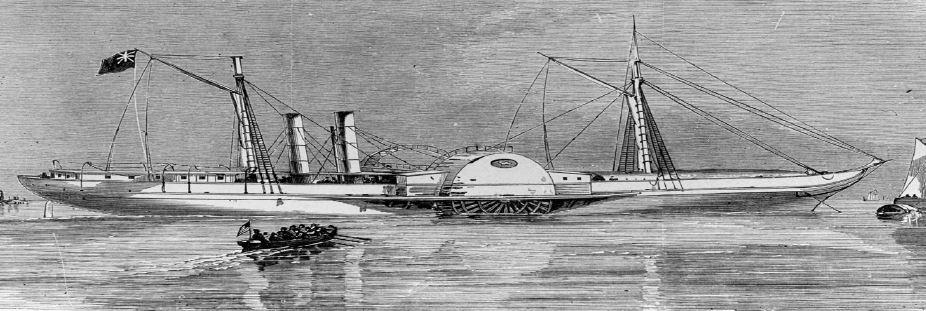

After the Civil War began, General Winfield Scott recommended to President Abraham Lincoln that Union naval vessels block southern ports so the Confederacy could not ship or receive any goods that would support their war efforts. The plan also called for the Union to take control of the Mississippi River. When the operation, called the Anaconda Plan, was launched, Union naval vessels patrolled Florida’s Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Newspapers referred to the Anaconda Plan as the Great Snake. These ships patrolled near Jupiter Inlet, searching for Confederate blockade runners coming or going through the inlet. Confederate-, British-, and Bahamian-owned ships, and those from other countries, would sail to Bermuda, the Bahamas, and Cuba carrying products such as cotton, molasses, and whiskey in exchange for war materials and soap, coffee, dry goods, salt, flour, and alcohol. When ships returned, they sailed through Jupiter Inlet and up the Indian River to various destinations.

The Union Naval Squadron responsible for patrolling Florida waters was the East Gulf Blockading Squadron headquartered at Key West. Union gunboats pursued Confederate ships to capture or destroy them. Sometimes the Union captured blockade runners, and sometimes blockade runners avoided capture and reached their destinations.

EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION

The Emancipation Proclamation was one of Abraham Lincoln’s most important acts during his presidency. Effective on January 1, 1863, it stated, “all persons held as slaves are and henceforward shall be free.” The order, however, applied only to the states in rebellion, not to those loyal to the Union. Although the proclamation did not eliminate all slavery in the nation, it did affect the war, because it allowed Blacks to serve in the Union army and navy. About 200,000 Blacks had served by 1865, when the 13th Amendment was ratified, officially ending slavery.

RECONSTRUCTION

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln gave an important speech in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, known as the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln stressed that all men are created equal. His words encouraged the North to fight harder to save the Union. On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. The end of the Civil War was a victory for all those who were against slavery.

After the war, the former Confederate States had to rebuild, in a period called Reconstruction. It was a time of uncertainty for everyone, especially in the southern states, which had been devastated by the war. The newly freed slaves found themselves without places to live or work. Many of them returned to their plantations to work as paid employees, but a lot of plantation owners did not have money to pay them. The solution was sharecropping. Poor farmers, both Black and white, paid plantation owners rent by giving them part of the crops grown on that land, or a share, instead of money. This system helped both the plantation owners and the freed slaves, but sharecroppers still barely made enough to live on.

To be readmitted to the Union, southern states were required to take certain actions: 1) to rewrite their constitutions, eliminating slavery, and 2) to pass the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted citizenship to all people born in the United States. Florida completed these actions and rejoined the Union in 1868.

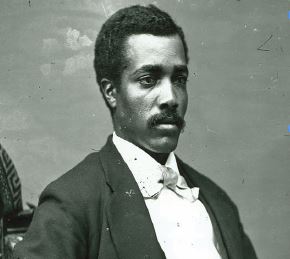

JOSIAH WALLS

After the Civil War, freed slave Josiah Walls worked as a teacher and at a sawmill in Alachua County. In 1868, he was a delegate to the Florida Constitutional Convention and served in the Florida Senate. Two years later, Republicans nominated Walls for Florida’s one seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In a close race, Walls won the election and became the first African American in Florida to be elected to the U.S. Congress.

- Why did Florida have to wait to become a state?

- What does “secede” mean?

- What kind of food did Florida provide to the Confederacy?

- What state capital, east of the Mississippi River, was never captured by Union forces?

- Explain sharecropping.

- Why did South Carolina and other southern states secede from the Union?

- What event did this action cause?

- What did the southern states have to do before rejoining the Union?

- Why was the lighthouse built at Jupiter Inlet?

- What did General Winfield Scott recommend to President Lincoln?

- What is a blockade runner?

- Who was Josiah Walls and why is he important?

- What was the purpose of the Anaconda Plan?

- Why was the Anaconda Plan called the “Great Snake?”

- What was the population of Florida in 1850?

- How many slaves were in Florida in 1850?

- What is slavery?

- What were the differences between the North and the South?

- Who was elected U.S. president in 1860

- Why did South Carolina secede from the Union?

- When did Florida secede from the Union?

- When did the Civil War begin?

- Why was the Civil War fought?

- How many Floridians fought in the war?

- How many Floridians lost their lives in the war?

- Who worked on the plantations during the war?

- How did Florida help during the war

- What city in Florida was not captured during the war?

Make a drawing or model of the Jupiter Lighthouse.