The Great Depression and World War II

FLORIDA IN THE GREAT DEPRESSION

The 1926 Land Bust, followed by devastating hurricanes in 1926 and 1928, eroded confidence in Florida’s economy and sent it into an economic depression. In October 1929, the stock market crashed, and the entire nation fell into the Great Depression, which would last until World War II. Also in 1929, Florida’s citrus crops suffered from a terrible infestation of the Mediterranean fruit fly, putting more stress on the economy.

During the years of the Great Depression, Florida benefited during the winter months from tourism and people who visited their second homes in the state. Those who built their own motor homes, called Tin Can Tourists, also visited Florida during the winter, although police checked visitors at the state border to be sure they could support themselves during their stay. Nevertheless, there was not enough income in Florida, its government had no way to provide relief work, and the state constitution prohibited deficit spending. Many people had no way to earn a living.

The Florida State Racing Commission, established in 1931, legalized gambling at horse and dog racing tracks and at jai alai frontons, which allowed the state to earn revenue from the taxes paid by winners. This action was not much help, however, because people did not have much money to place bets.

THE NEW DEAL

In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran for president, promising a New Deal for Americans. He said he would lower the unemployment rate and boost the economy. After his inauguration in March 1933, Roosevelt launched his initiatives across the country, called Alphabet Soup because they were known by their initials. Two programs that helped Florida by providing jobs were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

The CCC was created and brought to Florida in 1933, hiring more than 40,000 young men. They were put to work helping in many areas, including establishing new state parks and planting over thirteen million trees. When the Overseas Railroad was destroyed by the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, the CCC helped replace it with the Overseas Highway. This new road opened to vehicles in 1938, connecting Key West with the mainland. Parts of it are still used today.

The WPA created about 40,000 jobs for unemployed artists, musicians, writers, researchers, and teachers. Artists created colorful paintings for libraries, post offices, and other public buildings. Writers interviewed and recorded local people to collect history and stories. One writer, Zora Neale Hurston, was an anthropologist, folklorist, and novelist, traveling the South collecting stories and writing about its rural areas. Veronica Hull interviewed residents of the Conch community in Riviera Beach while photographer Charles Foster recorded their images.

In addition to these two programs, Florida’s industries began to grow again, helping the state’s economy. The citrus industry developed new ways to package and can fruit that allowed the fruit to stay fresh longer. Paper mills were built in several Florida cities, including Jacksonville, Panama City, and Pensacola. Finally, the aviation industry brought tourists to the state by planes. By 1939, three airlines operated in Florida. More tourists meant that more money was spent in Florida. President Roosevelt’s New Deal helped Florida’s economy prosper.

WORLD WAR II

World War II helped America, including Florida, recover from the Great Depression. Florida businesses produced war supplies. More than 250,000 Floridians joined the U.S. Armed Forces. The warm climate and flat land made the state a perfect place to train pilots and other soldiers. The military established bases throughout Florida, including Fort Myers, Lakeland, Vero Beach, West Palm Beach, Boca Raton, and Miami, providing job opportunities for local civilians.

During the war, thousands of troops trained or were stationed or in Florida. In 1941, Morrison Field in West Palm Beach became an army airbase. A year later, the army opened an airbase in Boca Raton and took over the Boca Raton Club, turning it into housing for military trainees. Florida hotels were used for military housing and hospitals. A Palm Beach oceanfront hotel, The Breakers, was converted into Ream General Army Hospital to treat wounded soldiers.

In 1942, the German navy began attacks using submarines along Florida’s Atlantic coast. German subs, called U-boats, torpedoed and sank or damaged ships carrying supplies to Europe. The Germans hoped their attacks would weaken the U.S war plan. Many of the U-boat attacks came at night. German submarines saw outlines of the American ships against the bright shore lights. Residents along the coast, therefore, had to dim or hide their lights behind curtains. To slow down the German U-boats, Civil Air Patrol squadrons patrolled the coastal waters. This effort helped to stop the German attacks along Florida’s coast by 1943.

While many Floridians were off fighting overseas, the rest of the residents helped with the war at home. They worked in the growing shipbuilding and farming industries. Women filled many jobs left by men who had joined the military, working on farms and factories in record numbers. They picked crops and packaged them to be shipped to the troops. Everyone in Florida worked to help end the war. Schools held contests to see who could collect the most scrap metal or paper to support the war effort.

MORRISON FIELD

In 1940, the U.S. Army Air Corps, forerunner of the U.S. Air Force, established Air Transport Command at Morrison Field, which had opened in 1936 west of West Palm Beach. The army added barracks and other buildings, and a hangar for 3,000 soldiers who would be stationed there during the coming war.

More than 45,000 troops either trained at or flew out of West Palm Beach for destinations around the world, including for the invasion of Normandy, France, on D-Day. As many as 250 women from the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) also served at Morrison Field. The 313th Material Squadron from Miami Municipal Airport moved to Morrison Field in 1942 to handle air cargo and maintain the airport and its aircraft. A thousand men worked around the clock to overhaul, repair, and test aircraft before returning them to service.

Military aircraft flew between Morrison Field and India, from which they made trips to China. This trip over the Himalayan Mountains, nicknamed “flying the hump,” took more than two weeks each way. The planes made stops in Puerto Rico, British Guinea, and Brazil before crossing the 1,428 miles of ocean to Ascension Island. From there, they stopped in Liberia, then flew up the west coast of Africa and across the Sahara Desert to French Morocco in North Africa, and on to India. Military secrecy demanded that Palm Beach County civilians had little idea of the importance of this command until after it was deactivated in 1947.

The Army Air Force established the 1st Air Weather Group at Morrison Field in 1946 to administer, train, equip, and organize the four squadrons that gathered weather information that were then assigned to the Air Weather Service. It had started its first squadron in Ohio in 1942. The 55th Squadron flew a B-29 over a hurricane for the first time from Morrison Field on October 7, 1946, with three photographers and a public relations officer on board to cover the event.

Morrison Field was deactivated in June 1947 and returned to Palm Beach County’s control. A year later, county commissioners voted to rename the facility Palm Beach International Airport, even though the community had mixed feelings about losing the name that held historical significance, and that thousands of former servicemen and women might choose to revisit.

From 1951 to 1953, part of the airport served again as an air force base, where 23,000 airmen trained during the Korean War. The base was deactivated in 1959 and returned to Palm Beach County once again. As air traffic has increased, the airport has been expanded to accommodate travelers. As a memorial to its service as a military base, the airport dedicated a new terminal in 1988 to U.S. Navy Commander David McCampbell (1910-1996), a lifelong resident of Palm Beach County and World War II flying ace who received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

BOCA RATON ARMY FIELD

By the time World War II began, both the U.S. Navy and the Army Signal Corps had developed techniques for air and ground radar (an acronym for radio detection and ranging). A radar post in the hills above Pearl Harbor spotted the Japanese attack in December 1941 but could not alert the main forces in time. The Signal Corps opened a radar school at Camp Murphy, now Jonathan Dickinson State Park in Martin County, and the Army Air Corps wanted a similar site nearby. They considered Vero Beach, but after campaigning by Boca Raton’s Mayor Jonas C. “Joe” Mitchell, the Air Corps’ Radio School No. 2 opened (No. 1 was in Illinois) on land that would become the site of Florida Atlantic University and Boca Raton Airport. About fifty owners of property totaling more than 5,820 acres, including the Town of Boca Raton and the Lake Worth Drainage District, were forced to sell their land to the U.S. government under the Second War Purposes Act. As explained in the Miami Herald on May 17, 1942, owners were notified “to vacate immediately all the land west of the railroad at Boca Raton. No financial offer has been made by the government to the owners of the land, but an appraisal is being made.”

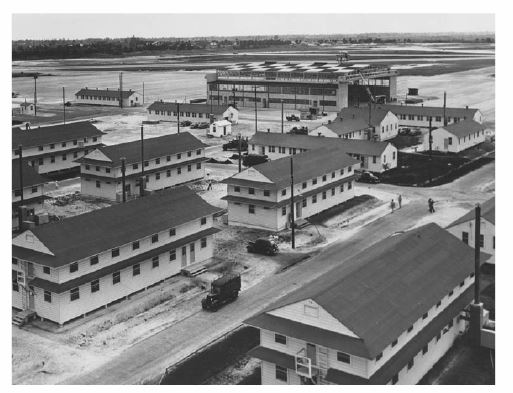

Boca Raton Army Air Field officially opened on October 12, 1942. The army constructed more than 800 buildings and four runways, where B-17 pilots trained and airplanes came from all over to have radar installed. Cadets sometimes spent up to twenty hours per day on academic and military training to learn engineering, aerodynamics, and communications. After finishing their education at Yale University, these cadets became commissioned officers.

The Air Corps also took over the luxurious Boca Raton Club to house trainees and officers attending the radar training school. Conditions were anything but elegant, however. The expensive furnishings had been replaced by standard army bunks housing eight to a room, and poor water pressure made bathing difficult, but no excuse was allowed in completing the rigorous schedule. When the club became too crowded, officials turned the grounds, including the golf course, into a tent camp.

Although Boca Raton’s population was only 723 in 1940, during the war years it increased by 30,000 servicemen and women, civilian employees, and their families. Over 100,000 troops passed through Boca Raton for training or en route to service in the Pacific or Europe. The activity created a boom for the area, as Boca Raton residents could not fill all the needs of the military alone. In 1944 the Boca Raton Club was returned to its owner and reopened as the Boca Raton Hotel and Club. The Boca Raton Army Air Field operated until 1947, when it closed.

BELLE GLADE POW CAMP

During World War II, the War Manpower Commission called for prisoner-of-war (POW) camps to be established in some states to fill the labor shortage caused by the draft. More than 9,000 German prisoners were sent to Camp Blanding near Starke, Florida. From there, the POWs were assigned to one of the twenty-two camps in the state. From March to December 1945, after picking oranges in the Orlando area, about 250 POWs were sent to a camp just east of Belle Glade, next to the Everglades Experiment Station. Another camp was located at Clewiston in Hendry County.

The prisoners and camp guards ate the same food, as required by the Geneva Convention. Years later some of the guards reported having had a mutual respect and camaraderie with many of their captives. Two weeks after arriving, however, the prisoners initiated a strike when their cigarette rations were reduced. Because Americans were beginning to hear about Nazi concentration camps at that time, national attention and congressional reactions led to thirty-nine “troublemakers” being returned to Camp Blanding. Strikers were restricted to bread and water until they returned to work.

Many POWs worked in a bean-canning factory or helped to build the Lake Okeechobee Dike. Others harvested sugarcane from before 8 a.m. to about 3 p.m., for which they were paid eighty cents a day. While temperatures over 100 degrees and snakes often made the fieldwork miserable, many of the Germans enjoyed hunting snakes to make souvenirs from their skins. When the Belle Glade camp closed, its flagpole was given to American Legion Post #20 at 101 S.E. Avenue D in Belle Glade.

1. What did the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) do for Florida?

2. What occurred in October 1929?

3. Who was Zora Neale Hurston?

4. Go online and research Hurston. Write a one-page report about her and her contributions.

5. List and explain the various ways the people and places of Palm Beach County helped the war effort.

- What does POW stand for?

- What school was at Boca Raton Army Air Field?

- The word radar is an acronym. What does it stand for?

- When did Morrison Field open?

- Why did the prisoners at Belle Glade POW Camp go on strike?

- What kind of work did the prisoners-of-war do?

- Why did the government take away people’s land to build Boca Raton Army Air Field?

- An airplane from the 55th Squadron, 1st Air Weather Group, made a special flight in October 1946.

What kind of airplane was it? What did it do for the first time?