Colonial Florida

Click below for a downloadable copy of this article.

THE FIRST SPANISH PERIOD

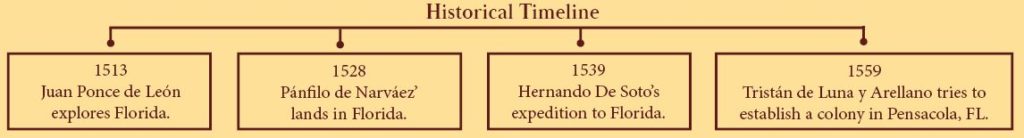

The first explorers authorized by the Spanish government arrived in Florida in the sixteenth century. When they encountered the native peoples, they found most of them to be hostile. Between 1513 and 1565, the Spanish made many attempts to establish permanent settlements in Florida, but they were not successful until Pedro Menéndez de Avilés established St. Augustine in 1565.

The King of Spain authorized Juan Ponce de León to search for the land called Biminis, promising Ponce he would be governor of any new lands he might find. Ponce paid to outfit three ships and set sail on March 3, 1513, from Puerto Rico with sixty-five people, including two free Africans, two Indian slaves, one white slave, and one woman. The explorers found what they thought was an island on April 3, 1513, which Ponce de León named La Florida for the Pascua Florida, or feast of flowers, celebrated at Easter. Sailing further south along the coast, Ponce made another discovery—the speedy Gulf Stream current—which ships would later follow to take treasures to Spain. Ponce continued south past Miami Beach, west through the Florida Keys, and north to the barrier islands near Fort Myers, where he had a small skirmish with the Calusa Indians. Then he backtracked to Puerto Rico, arriving on October 19, 1513. Ponce was awarded a knighthood for his exploration.

In 1521, Juan Ponce de León returned to Florida with 200 settlers and started a Spanish colony on the west coast. Before long, the Calusa attacked the colonists. Many were killed, and Ponce was wounded. He sailed for Cuba, where he died of his injuries. Leon County, Florida, is named in his honor.

Other Spanish conquistadors tried to explore Florida, but they were also unsuccessful. In 1528 an expedition of five ships and 600 men, led by Pánfilo de Narváez, sailed into Tampa Bay. His attempt to establish a colony failed, and he and most of his men died. The survivors worked their way along the Gulf Coast for eight years in an attempt to reach the Pánuco province of New Spain, now known as Mexico. Four survivors made it, including Esteban, a Black slave. During this journey, Esteban gained knowledge that he would later use to lead Spanish explorers through what became the southwestern United States. Another survivor, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, returned to Spain and wrote about the journey.

HERNANDO DE SOTO

Hernando de Soto was born in Spain around 1500 to a family that was poor but part of the Spanish nobility. After obtaining some education at university, he was invited to join an expedition to the Indies in 1514, where he and his compatriots explored territories that now comprise Panama, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Later, as second in command during Francisco Pizarro’s conquests of Peru and the Incan capital of Cuzco, de Soto increased his wealth.

After earning his fortune, de Soto returned to Spain and led a life of leisure until he left to conquer Florida in 1539. He landed in Tampa Bay and explored central Florida. De Soto and his men became the first Europeans to see the Mississippi River. He died during the trip and was buried in that river, but the rest of his men made it to New Spain. Hernando County, De Soto County, and the De Soto Trail are named in his honor.

TRISTÁN DE LUNA y ARELLANO

Tristán de Luna y Arellano of Spain is known for a short-lived colony at the site of Pensacola, Florida. De Luna arrived in the New World in 1530-1531 and in 1540 joined the Coronado expedition, which explored what became the southeastern United States and New Spain (Mexico). The viceroy of New Spain chose de Luna to establish a colony on the Gulf Coast and named him governor of Florida. Five days after landing at Pensacola Bay, however, a hurricane destroyed most of the ships and supplies. The colony barely survived until 1561, when de Luna was ordered back to Spain. He died broke in Mexico City in 1573.

JEAN RIBAULT CLAIMS FLORIDA FOR FRANCE

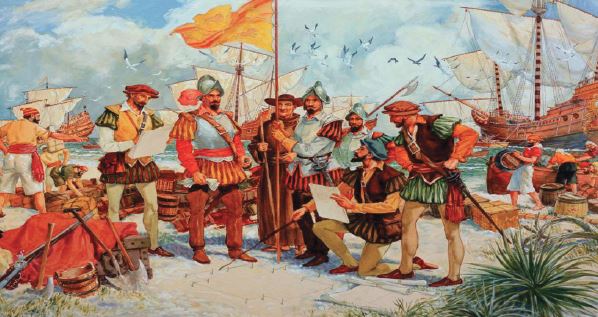

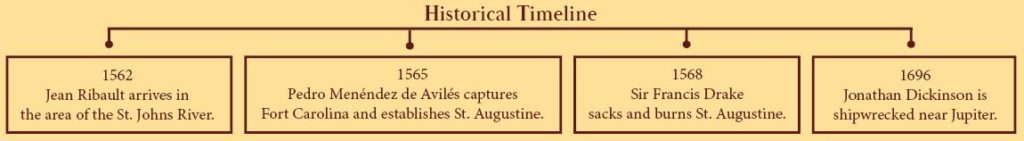

In 1562 French explorer Jean Ribault visited Florida to claim land for France. At the mouth of the St. Johns River, he built a monument to mark his claim. He then continued north and built a fort on the Carolina coast. Ribault left thirty men there while he returned to France for supplies. The men at the fort had many problems but were rescued by a passing British ship.

Two years later, another Frenchman, René Goulaine de Laudonnière, led 300 men and four women to establish a Florida colony. He built Fort Caroline near present-day Jacksonville, but the colonists ran low on food and were unhappy with Laudonnière’s leadership. Just as they decided to leave, Ribault arrived with 500 men, seventy women, and supplies, saving the French colony. The King of Spain soon sent Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to drive the French out. Ribault was warned by friendly native peoples that the Spanish were going to attack and sailed south with most of his men. The Spanish killed those who remained at Fort Caroline, then caught up with Ribault and killed most of the French. Laudonnière survived, however, and made it back to France. The location where Menéndez killed Ribault and his men became known as Matanzas, which means massacre.

THE BIRTH OF ST. AUGUSTINE

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés built a wooden fort when he landed in Florida. On September 8, 1565, he officially named the settlement St. Augustine. It became the first permanent city in the United States and is considered the oldest city in the continental United States. St. Augustine was established forty-two years before Jamestown, Virginia, and fifty-five years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock.

CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS

From 1672 to 1695, the Spanish built a stone fort they called Castillo de San Marcos to protect St. Augustine, the first permanent settlement by Europeans in the continental United States (established in 1565). It still remains and is open to the public. The star-shaped Castillo de San Marcos covers about 20.5 acres. The walls are about fourteen feet thick and thirty feet high. The interior plaza is one hundred feet square, and a forty-foot moat surrounds the fort. A type of stone called coquina (Spanish for little shells) was used to build the fort. Coquina is made up of ancient shells bonded together over time. The local stone was quarried on Anastasia Island and transported to St. Augustine. An enemy force has never succeeded in taking the Castillo. The British tried and failed in 1702 and in 1740. They only gained control of the fort when Spain turned it over to Great Britain under the 1763 Treaty of Paris at the end of the French and Indian War.

FORT MOSE

In the late seventeenth century, slaves from Georgia and South Carolina escaped to Spanish Florida. The King of Spain allowed the runaways to settle at St. Augustine if they became Catholics and pledged their loyalty to Spain. In the early eighteenth century, former slaves established Fort Mose just north of St. Augustine. About a hundred men, women, and children lived there in the first free African American community in the United States. The men worked as farmers, carpenters, and ironsmiths, and formed a militia that helped defend the Spanish from attacks by the British and native peoples. Nonetheless, in 1740 the British governor of Georgia, James Oglethorpe, succeeded in destroying the fort. It was rebuilt, but in 1763, when the British took control of Florida, the remaining residents abandoned it.

FLORIDA AS A BRITISH COLONY

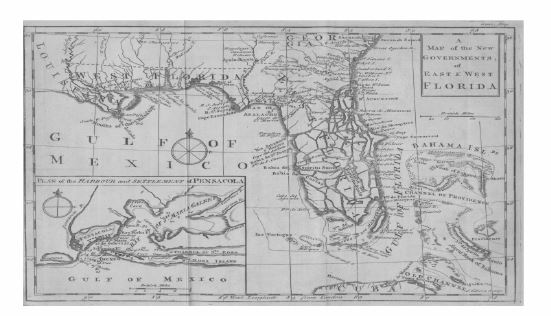

From 1754 to 1763, the French and Indian War was fought in North America. The British colonies fought the French and their native allies over territory. In 1763, the war ended when the Treaty of Paris was signed. During the war, Britain had captured Havana, Cuba, so the Spanish traded Florida to Britain to get it back. The British divided Florida into two territories—East Florida and West Florida—so it would be easier to govern.

EAST FLORIDA

East Florida stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Apalachicola River, with St. Augustine as its capital. The region had good soil, so it was excellent for farming. To attract settlers there, the British government offered land grants; grantees would receive land if they farmed it. The settlers also had to agree to defend the new territory. Archaeologists have found evidence that some English settlers in the eighteenth century may have stayed at Grenville Inlet, which today is known as Jupiter Inlet.

WEST FLORIDA

West Florida stretched from the Apalachicola River to the Mississippi River, including parts of modern-day Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Pensacola was its capital. Sandy soil made farming difficult. West Florida earned most of its money through the sale of animal fur and lumber.

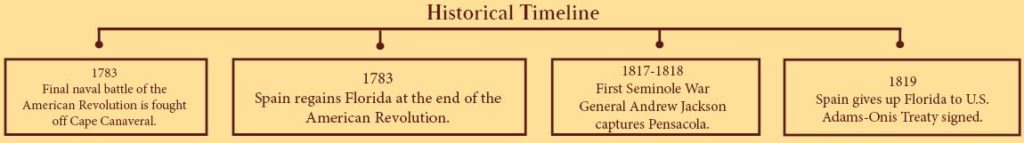

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

The British did not rule Florida for long. The northeastern colonies did not like British rule and began a war known as the American Revolution. The colonists who fought for independence were called Patriots, and those who sided with the British were called Loyalists because they were loyal to Britain. Florida did not have problems with Britain. Many English settlers in East Florida invited Loyalists from South Carolina and Georgia to move to Florida. Most of the American Revolution took place far north of Florida. While Britain was busy fighting the colonies, Spain invaded West Florida and defeated the British.

THE SECOND SPANISH PERIOD

On September 3, 1783, a second Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the American Revolution and giving the American colonies their independence. It also gave Florida back to the Spanish. Even though the Spanish again had control of Florida, new Americans flooded into the territory. At first they were searching for runaway slaves, but later they came there to live. Problems between the Americans and the Seminoles living in Florida led to the First Seminole War (1817-1818). When the United States invaded Spanish territory to fight the Seminoles, it weakened Spain’s control. In 1819, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and Spanish Minister Luis de Onis signed the Adams-Onis Treaty. This agreement gave Florida to the United States and in return, the United States cancelled the $5 million debt that Spain owed the United States. This treaty was ratified by the United States in 1821.

- Were the Spanish successful in their first attempts to settle Florida? Why or why not?

- Who was Esteban, and why is he important to Florida history?

- Why did Menéndez go to Florida?

- Who built St. Augustine?

- How did Spain win control of Florida back from the British?

- What other present-day states were part of British West Florida?

Why do you think the Calusa attacked the Spanish?

On a map, draw where East Florida and West Florida were located.