Territorial Florida

Seminole Wars | Territorial Florida

This section provides an overview of Florida while it was still a Territory and the Seminole Wars.

Click below for a downloadable copy of this article.

TERRITORY OF FLORIDA

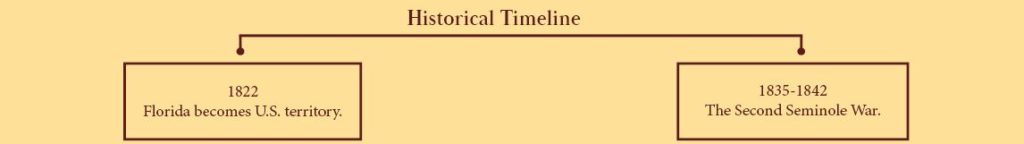

Florida became a territory of the United States on March 4, 1822. A territory is an area of land under the jurisdiction of a ruler or state. The territorial legislature established Florida’s first two counties, Escambia (formerly British West Florida) and St. Johns (formerly British East Florida). The legislators also established the capital at Tallahassee, because it was midway between St. Augustine in the east and Pensacola in the west. Florida would remain a territory for another twenty-three years.

In 1838, fifty-six men held a special Florida Constitutional Convention and wrote Florida’s constitution, or plan of government. A territory could not become a state, however, until its population reached at least 60,000, and there were not yet that many people living in Florida. Problems with the Seminoles had caused many people to move away and kept others from moving into Florida.

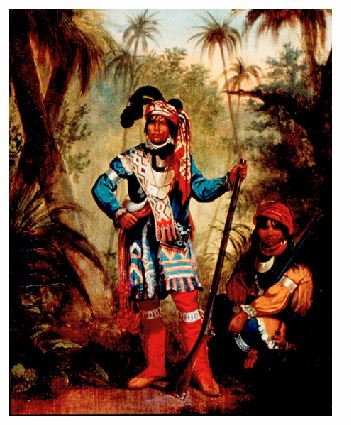

THE SEMINOLES

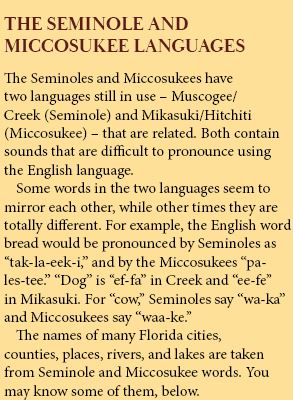

Florida has been home to the Seminoles since the 1700s, when Spain controlled Florida. When Florida’s original native population declined, the Seminoles came here from the Creek tribes in Georgia and Alabama. They were pushed south from their homeland because white settlers wanted their lands. Eventually the Miccosukees and the Seminoles became the two dominant tribes in Florida. Though they are from the same cultural group, they speak two different languages. The name Seminole could have two meanings. From the Creek phrase phegee ishti semoli, Seminole means wild men. From the Spanish word cimarrones, Seminole means runaways.

Both the Seminoles and Miccosukees came into conflict with Florida’s white population. The Seminoles fought three wars with the United States. The First Seminole War (1817-1818) began because Seminoles in Spanish Florida made raids into the United States. Also, slaves from Georgia and Alabama escaped into Florida and began living with Seminoles. General Andrew Jackson led U.S. forces across the border into Florida to fight the Seminoles. He captured several Spanish towns and executed two British citizens because he thought they were spies, but he was unable to stop the Seminoles. In the 1820s, American settlers entered Florida and clashed with the Seminoles over land. As a result, in 1823 the territorial government of Florida signed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminoles, which required the natives (1) to give up their land and settle on four million acres of land in central Florida, and (2) to stop allowing runaway slaves to live with them.

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson—the same man who had, when he was a general, tried to stop the Seminoles in 1817-1818—signed the Indian Removal Act. The law required all Native Americans to move to the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), west of the Mississippi River. Many Seminoles did not want to leave their homes. A group of tribal leaders went to see the place where the Seminoles were to relocate and were persuaded to move there. However, when they returned to Florida, many of the chiefs told their people they had been forced to agree. Seminoles continued to refuse to leave Florida, which led to the Second Seminole War (1835-1842)

Osceola was one Seminole who refused to leave his Florida home. In December 1835, he led a small group of warriors that killed a government agent who had once put Osceola in jail. On the same day, a large group of Seminoles attacked Major Francis L. Dade and over 100 soldiers traveling from one fort to another. Only three of Dade’s men survived. Osceola was eventually captured, and died in a South Carolina prison in 1838.

Colonel William Jenkins Worth brought the war to an end in 1842, but no treaty was ever signed. Most of the Seminoles were either killed or captured and sent west to Indian Territory. A few hundred Seminoles retreated to the Everglades in south Florida. About 1,500 soldiers died and $20 million was spent in the Second Seminole War.

Once there was peace in Florida, settlers felt safe enough to move there. They started farms and businesses without fear of Seminole attacks. The territory’s population soon reached 60,000, so Florida could enter the Union. On March 3, 1845, Florida became the twenty-seventh state.

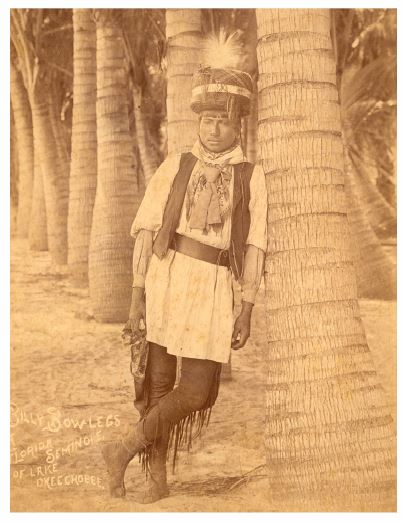

Ten years later, the Third Seminole War (1855-1858) began after a military survey team destroyed banana trees in Chief Billy Bowlegs’ garden in Big Cypress Swamp. When Bowlegs confronted the men, they refused to either pay for the damage or apologize. The next day, the Seminoles attacked the survey team, killing or wounding all of them and starting the war. In 1858 Bowlegs’ band was forced to surrender and move to the Indian Territory, but the rest of the Seminoles refused to surrender. They moved deeper into the Everglades. Some of the Seminoles and Miccosukees who live in Florida today are descendants of these warriors. After many years of hiding out in the swamps, Seminoles were able to rebuild their lives in south Florida. They have become part of Florida’s modern society and economy, involved in farming and ranching, and operating hotels, casinos, and other tourist attractions.

BLACK SEMINOLES

When the British took control of Florida in 1763, runaway slaves who had lived free under Spanish rule moved to Cuba. Those remaining in Florida lived with Seminoles as others before them had done. Some were slaves of the Seminoles; others were free, but all were called Black Seminoles. Even though the Seminoles protected the Blacks, slave owners from the north came after them and tried to return them to their plantations. Sometimes Seminoles lied, saying they owned a free black man in order to protect him. The Black Seminoles accepted the culture of the Seminoles. They spoke the language, and they dressed like Seminoles. The Black Seminoles were helpful because they knew about farming, shared their crops, and served as interpreters because they spoke English.

Some Black Seminoles rose to important positions in the tribe, such as Abraham, a former slave who had been freed by the British during the War of 1812. Abraham then lived in the towns along the Suwannee River, where Seminole Chief Micanopy protected him as an important interpreter and counselor. Abraham was part of the Seminole delegation that visited Washington, D.C. in 1826. He was one of two interpreters at the 1832 Treaty of Payne’s Landing, which forced the Seminoles to leave Florida.

During the Seminole wars, Black Seminoles joined the fight against the United States to keep their freedom. The ones that were caught—mostly during the Second Seminole War—were returned to slavery or sent to the Indian Territory with the Seminoles. A few fled to the Bahamas to avoid capture, where their descendants live today.

Black Seminoles later left the Indian Territory for Mexico or Texas. In the 1870s and 1880s, the U.S. Army enlisted Black Seminoles to fight other native tribes and four Black Seminoles were awarded the Medal of Honor. Today, descendants of the Black Seminoles live in Florida, Oklahoma, Texas, and Mexico.

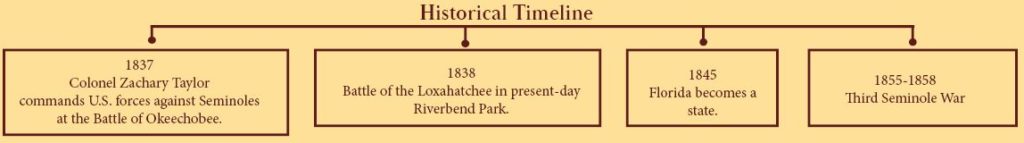

JOHN HORSE

Born to a Seminole father and African mother, John Horse (1812-1882), also known as John Cavallo, became a Black Seminole leader during the Second Seminole War. In 1837 he was captured under a white flag of truce with Osceola, Coacoochee and other Seminoles. They escaped from prison at Fort Marion in St. Augustine. That December, when Colonel Zachary Taylor’s troops fought Seminole warriors at the Battle of Okeechobee, John Horse led the Black Seminoles among the Seminole force. He later surrendered and was sent to the Indian Territory. He then led a group of Black Seminoles into Mexico. Before he died, John was able to obtain land for his people from the Mexican government.

SECOND SEMINOLE WAR IN PALM BEACH COUNTY

A few years after the Second Seminole War began, fighting erupted in what is now Palm Beach County. In January 1838, Navy Lieutenant Levin Powell headed a small group of soldiers and sailors down the Indian River and onto the Loxahatchee River. They encountered a large group of Seminoles west of today’s Florida’s Turnpike in Jupiter, now known as Loxahatchee Battlefield Park. The Seminoles forced the Americans to retreat, and men died on both sides, including one Black Seminole. Soon after, Major General Thomas Jesup led U.S. forces against the Seminoles near the same location and the Seminoles withdrew, after wounding and killing many soldiers.

After this battle, the soldiers moved a few miles east and built Fort Jupiter on what is now known as Pennock Point, about three miles from Jupiter Inlet. The fort closed in 1842 and reopened in the 1850s for the duration of the Third Seminole War. Jesup tried to end the Second Seminole War by suggesting that the remaining Seminoles move into south Florida to stay, but the government rejected his idea. He was ordered to capture all Seminoles who had gathered at the fort to await the government’s response. Of the 678 Seminoles taken, 165 were Black Seminoles.

During this war, several forts were established on the east coast of Florida to supply the military. In 1838, Major William Lauderdale led volunteers and soldiers south to the New River, hacking a supply trail out of the jungle to reach their destination. When they arrived, they constructed a fort that Jesup named Fort Lauderdale. The trail they had forged between the coastal swamps and the Everglades became known as Military Trail, which today runs through Palm Beach County.

COACOOCHEE

Coacoochee (Wild Cat) was the son of King Philip, chief of a Miccosukee band in Mosquito County, Florida. General Joseph Hernandez captured Coacoochee with Osceola and others in 1837 at a meeting held during a truce. He escaped with other Seminoles, and he and his warriors participated in the Battle of Okeechobee on December 25, 1837. He later surrendered and moved to the Indian Territory. After he failed to be appointed chief of the Seminoles in 1849, he led his band of Seminoles and Black Seminoles into Mexico, where they were welcomed.

- Where did the remaining Seminoles go after the end of the Second Seminole War?

- Who was Osceola?

- What is the meaning of “Seminole”?

- How many wars did the Seminoles fight against the U.S.

- Which war was the most costly?

- Why did runaway slaves come to Florida?

- Who was Lake Worth named after?

- How did General Thomas Jesup try to end the Second Seminole War?

Wonderful article of little known local history.

Thank you for educating me.