This article originally appeared in the Winter 2015 issue of Tustenegee as "Mrs. Martin Majewski Brewer: An Oral History." It has received minimal editing.

Introduction

Mary Louise Majewski Brewer (1891-1971) was taped at the Brewer home, 307 Wildemere Road, West Palm Beach, Florida, on March 29, 1962, by Rush Hughes for the Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Lise M. Steinhauer of History Speaks transcribed the taped oral history in 2006. This interview is part of the ongoing Oral History Project of the Historical Society. Please consider the culture of the era in which these interviews took place.

HUGHES: Mrs. Brewer, when did you get here?

BREWER: I got here in the spring of 1895.

HUGHES: How old were you then?

BREWER: About four, four and a half.

HUGHES: [laughs] This is a sneaky way of finding out what your age is now, you see.

BREWER: [laughs] Yes, isn’t that?

HUGHES: Who were your father and mother?

BREWER: Mr. and Mrs. [Mary Louise] Albert Majewski.

HUGHES: And where’d you come from?

BREWER: We came from Jacksonville [and originally from South Carolina.]

HUGHES: You don’t remember much about when you were four years old, but I have a sneaking suspicion you picked up your recollections pretty early, didn’t you?

BREWER: Yes, I did.

HUGHES: What’d your family do?

BREWER: My father was a baker by trade. We had a bakery on Clematis Avenue for about eighteen years. But when he came down from Jacksonville, of course, he came down to work for someone else. At that time, Flagler had just built the[Royal] Poinciana Hotel—that is, a very small portion of it—and was getting ready to build the [Wayside] Inn, which was later called [the Palm Beach Inn, and then] The Breakers. And he ran this excursion from Jacksonville to bring the workmen, of course, to build the hotel. My father preceded us here, because West Palm Beach at that time was just a city of tents, and we were a family of five at that time. It would’ve taken a pretty good-sized tent to put us all in so he came down ahead to build a small home for us. We came down on the excursion; my mother brought us herself. By the way, I imagine it was as big an excursion as ever pulled into West Palm Beach, which, at that time, was the end of the line. And my mother bought a ticket for herself and five children for $2.50.

HUGHES: Sum total? [laughs]

BREWER: Sum total. And when she got here, she sold the return half of the ticket for $1.25, which meant that six of us got here for $1.25.

HUGHES: Your mother was a splendid businesswoman.

BREWER: Wasn’t she?

HUGHES: That bakery that you had for so long on Clematis Street, if your family had it eighteen years, that property must have increased in value considerably.

BREWER: Yes, it did. My mother bought it for $600 and paid for it $25 a month. And even at the $25 a month, it was tight squeezing at times to get the $25. And she held it eighteen years and sold it to Ewing Graham for $50,000 [in 1920]. And he held it five years and sold it for $125,000.

HUGHES: Oh, for heaven’s sake! Who bought it?

BREWER: The Woolworth interest.

HUGHES: Is that where the Woolworth store is now?

BREWER: That’s where the Woolworth ten-cent store is now. Mm-hmm.

HUGHES: Well, that was quite a rise. You mentioned being five in family when you came here. Did your mother have more children after you got here?

BREWER: Yes, there were four children born here.

HUGHES: And she ran a bakery besides.

BREWER: Mm-hmm. Before she had the bakery, she had the very first ice cream parlor in town.

HUGHES: That must have been a center of social activity.

BREWER: Yes, it was. There were three young men at the time that used to come by nightly. I think they were thinking once of mother and maybe twice for themselves because they would come and play the mandolin and guitar and sing and draw a crowd, of course. And they knew always that they were going to end up with a pretty good-sized dish of ice cream.

HUGHES: This was homemade ice cream?

BREWER: This was homemade ice cream that was churned every day, and I remember so well the old-fashioned freezer. One of us would churn, and one of us would sit on the top of it. And when it was ready, of course, the dasher would come out. We would always want what was left on the dasher, and Mother at times cleaned the dasher pretty well, you know.

HUGHES: [laughs] This was a great American custom, licking that paddle.

BREWER: Yeah, indeed it was.

HUGHES: What flavors did she have?

BREWER: Oh, vanilla. If strawberries were in season, we’d have fresh strawberry ice cream. If peaches were in season, we’d have peach ice cream.

HUGHES: I can still taste it. Wonderful stuff.

BREWER: Yes, it was.

HUGHES: Were there other stores in that area at the time?

BREWER: Not too many. In fact, when Mother bought her place where the Woolworth store is now, it was really considered far out because the business in the early days was on Narcissus until they had a fire. I can’t remember the year they had the fire. But after that, business moved down on Clematis Avenue.

HUGHES: In those years, I presume the Fire Department was a voluntary affair.

BREWER: Yes, it was. The first one that I remember—and I think there was one before that—Oscar Cheatham was the chief. Alfred Sadler, who later became chief, was in it, and Joe Borman, Bertie Scott, Bob Baker, Carl Kettler, [brother] Frank Majewski, Charlie Barfield, Clyde Merchant, and a few others.

HUGHES: What was the motor power? Horse, or did they have an automobile? Or they pulled it.

BREWER: Hand pulled, mm-hmm, must’ve been.

HUGHES: Do you recall the first automobiles?

BREWER: The first automobile that I can think of was an electric one, and I remember we’d hear it, and if we had a customer in the store, we left the customer and went to the front door. Everybody did, to watch that automobile come down the street. It was owned by a German couple on Evernia Street that wintered here, and oh, it was very fancy. They had little flowers on the sides, little artificial flowers.

HUGHES: Speaking of wintering here, I heard a story about somebody who lived in a tent on Clematis one winter.

BREWER: Oh yes, yes, I must tell you about that. This Mr. and Mrs. . . . [whispers] Can’t think of the name.

HUGHES: [laughs] That’s all right.

BREWER: But anyway, it was the aunt and uncle of Miriam Stowers, that everyone knows. He was professor at a girls’ college in Massachusetts and had a nervous breakdown, and the doctor ordered him south for his health. So they pitched a tent on Clematis Avenue, right across the street from our bakery, and lived there the entire winter.

HUGHES: [laughs] Well, of course, when West Palm Beach was first formed, tents were in fashion, weren’t they?

BREWER: That’s right. And for some reason or other, I don’t think it was as cold.

HUGHES: They didn’t get caught by a hurricane. That would’ve taken care of the tents. [laughs]

BREWER: The tents, wouldn’t it, yeah. Of course, I can’t remember the tents at all.

HUGHES: Was it the social thing to do to go meet the trains?

BREWER: Yes, indeed. If you didn’t see anyone all week long, why, if you’d go to the train Sunday night, you were sure to see everyone. I used to often think, people on the train must’ve thought this was a pretty big town if they judged the size of the town by the size of the crowd at the station.

HUGHES: Was there mail service? You had to go to the Post Office.

BREWER: Oh, yes,the first Post Office that I remember was in the Palms block. The Palms Hotel was on Narcissus and Clematis. We had a Post Office there and a grocery store on the corner and a millinery store and a jewelry store, and I think a watch repairing store. Mr. Idener, by the way, gave concerts down in the park with his gramophone.

HUGHES: Oh? The old Edison?

BREWER: The old Edison, yes. Everybody would go down to the park Friday nights, if I remember rightly, and he very graciously entertained them with his gramophone.

HUGHES: What were the favorite songs of the day?

BREWER: Oh dear, I don’t know. “After the Ball Was Over” maybe. “Let’s Break the News to Mother.”

HUGHES: Oh dear, oh dear, that does go, doesn’t it? Was this the kind of gramophone that had round cylinders?

BREWER: Round cylinders, mm-hmm.

HUGHES: The forerunner of the modern-day jukebox.

BREWER: That’s right, uh-huh. And Mrs. Saunders, who collected antiques, this gramophone ended up at her place.

HUGHES: Is she still in business?

BREWER: Oh, no, no, she died many years ago and donated the land where St. Mary’s Hospital is.

HUGHES: The reason I ask is because I know the Historical Society would love to have that.

BREWER: Wouldn’t they though?

HUGHES: You had doctors here?

BREWER: Yes, we had two doctors. Dr. Potter was our family physician, who had his office at the foot of Gardenia Street, if I remember right, a little place there. And later on we had Dr. H.C. Hood.

HUGHES: Any hospital facilities in the early days?

BREWER: Oh, no, none at all.

HUGHES: What happened if a hospital was required? Was operating all done at home?

BREWER: Must’ve been.

HUGHES: Strange enough, mothers must have been pretty good at taking care of medical ills in those days, of necessity.

BREWER: That’s right.

HUGHES: And I’m not sure that youngsters got ill as often as they do now, for some reason.

BREWER: I don’t think they did.

HUGHES: Did you have any dental service?

BREWER: Well, the very first dental service we had was a floating dental parlor that made the rounds of the east coast. He would pull in here and tie his houseboat up at the Holland dock. He’d send notice ahead, you know, that he was going to be here at a certain time. He would stay here perhaps a couple of weeks and then move on further south.

HUGHES: Do you have memories of having gone to see him? [laughs]

BREWER: Yes, indeed, I went down one day to have a small cavity taken care of and he put me in the chair. I was a little bit of a thing. I don’t suppose I was more than seven or eight, and he put me up in this great big dental chair. And I think one thing that frightened me was the movement of the boat. And pretty soon he got out this great big piece of rubber and a puncher to punch holes in it, and started putting it over my mouth. It frightened me to death. I started to kick and scream, and that was the last he saw of me. As far as he knows, I may be running yet! [laughs]

HUGHES: [laughs] He didn’t want any part of you, eh?

BREWER: Dr. Liddy was the next dentist, who had his office on Clematis Avenue in a building that had been used as a bank. And now I think Johnny has it—Johnny’s Playland, on Myrtle Avenue?

HUGHES: Oh yes.

BREWER: Mm-hmm, the building was moved. from Palm Beach over to Clematis Avenue.

HUGHES: What was the first church here?

BREWER: [pause] Well now, I don’t know. The Congregational, St. Ann’s, and the Methodist church—when Flagler first came here, he donated land for each church. The first Episcopal church was in a small building about where Newberry’s store is at present. The Methodist church was on the corner of Datura and Dixie. The Catholic church was in a building next to where the Alma Hotel is. And later on, about 1900, it was moved over to the present site and it’s still there, used as a little church office. The Baptist church was on Clematis Avenue about where that theater that was just taken down. Those were the four.

HUGHES: Where’d you go to school?

BREWER: I went to school on the corner of Clematis and Dixie in the schoolhouse that was, when the county was divided in 1909, used as the first courthouse.

And then the school was built up on Hibiscus Street at its present location. Mr. [Guy] Metcalf, who was on the School Board at the time, certainly was in a lot of disfavor, because the parents of the children were all frightened to death to think that their children had to go so far out in the country through wilderness to get to the school.

HUGHES: And across the railroad track, too?

BREWER: Yes, indeed.

HUGHES: Where was the cemetery?

BREWER: The cemetery then was where the Norton Art Gallery presently stands. It was called the Lakeside Cemetery.

HUGHES: Was there a road out to it or did they come by boat?

BREWER: Well, there was a shell road.

HUGHES: And when the cemetery was moved, were the bodies exhumed?

BREWER: Some of them were, and some of them preferred to let them stay there.

HUGHES: Is there anything else you remember that I haven’t gotten around to asking? Oh, how about the first airplane? Do you recall an airplane in here? [sound of airplane can be heard]

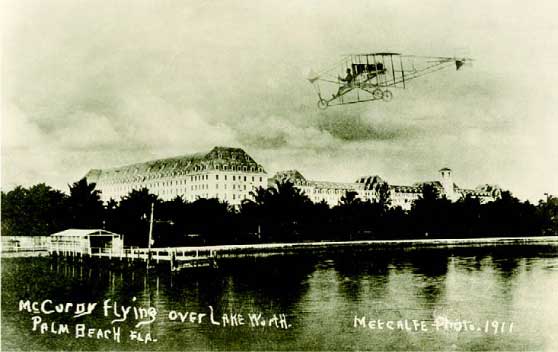

BREWER: Well, it was called a “biplane.” A fella by the name of McCurdy brought it to town and it looked very much like an egg crate. Mr. Currie used it in advertising his first auction sale, Bethesda Park, and McCurdy used Bethesda Park as his landing field.

HUGHES: Oh, and he stunted, was that the idea, or took passengers up?

BREWER: Took passengers, those that would dare go up with him, you know.

HUGHES: You ever get a ride?

BREWER: No, I never did. I won a ride on it, but I gave it to someone else. The day that I was supposed to get the ride, or the three contestants that were advertising this auction sale, the weather was very windy. Mr. Currie decided he didn’t want to take the chance of letting three young people go up in the plane, so he gave each one of them a check for $75. Which I lost out on because I turned mine over to someone else!

HUGHES: I bet you’re still mad about that? [laughs]

BREWER: [laughs] Yes, I am. And Joe Jefferson turned on the switch.

HUGHES: To turn the lights on?

BREWER: To turn the lights on.

HUGHES: Joe Jefferson, the stage star?

BREWER: The stage star. He was very prominent at that time on the Broadway stage. He played the part of Rip Van Winkle.

HUGHES: Now how did he get in on this? Who invited him down to perform this service?

BREWER: Well, his sisters had a winter home here, and he used to come down and spend quite a bit of time.

HUGHES: What had the lights been before that?

BREWER: They had been gas lights, the acetylene lights that had to be lighted.

HUGHES: So the lamplighter came around.

BREWER: The lamplighter, mm-hmm. Had to be lit each night. I remember so well watching him. That was a big event each night, to watch him turn on the lights.

HUGHES: You had to be in the house by that time, didn’t you?

BREWER: Well, at that time we were in the midway of the block, so I could even go out front and watch it practically now.

HUGHES: Seems to me, those lights collected a lot of bugs.

BREWER: Yes, I remember those great big old bugs. I don’t know what you call them. I was scared to death of them. I stayed clear of them.

HUGHES: Who formed the telephone?

BREWER: Dr. Liddy owned the first telephone company, which he later sold to M. E. Gruber, and then M. E. Gruber sold to the Bell Telephone people.

HUGHES: There couldn’t have been very many subscribers in those years.

BREWER: Not too many, no. I think by 1906 they had forty-two subscribers. I know when they were putting the system in, my mother asked to have number one, and Dr. Liddy said that he was sorry but he’d already promised number one to Mr. Currie. But if she wanted, she could have number two, which was our telephone number for a good many years. And the little switchboard was in Dr. Merrill’s Drug Store, which is about next to Belk’s store at the present time. I later, in fact, worked over on the switchboard.

HUGHES: Oh? Do you remember who the first operator was?

BREWER: [pause] No, I don’t.

HUGHES: Like Fibber McGee, you know, used to say, “Hi Marge.” [laughs] Everybody knew the operator by first name.

BREWER: Yeah, that’s right.

HUGHES: A hand-cranked machine.

BREWER: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

HUGHES: Did they get out of order, or did they work pretty well?

BREWER: Well, fairly well.

HUGHES: Were there party lines?

BREWER: Oh yes, party lines, mm-hmm.

HUGHES: How many people on a line? [laughs] Everybody?

BREWER: Well not as many as they have now, of course, because with only so few in town—

HUGHES: They ever have any problems with getting the people off in case of an emergency? Seems to me we have that more now than we used to.

BREWER: Oh yes, I think people were a little bit more solicitous of each other.

HUGHES: And they knew each other.

BREWER: Oh sure, everybody knew each other.

HUGHES: Aside from the gramophone concert on Fridays and the nightly concert in the ice cream parlor, what was the entertainment in the area?

BREWER: Well, there wasn’t too much, tell you the truth. After the Fire Hall was built on the corner of Dixie and Datura, they had weekly dances at the Fire Hall, which was a big event. And sometimes, in the middle of the week, we’d have what we called a “practice dance.” We’d go up there and take maybe a gramophone or something, and it was a dance right on but we just called them “practice dances.” Getting ready for Friday night, see?

HUGHES: Who played for the Friday night dances?

BREWER: Well, there was a little Negro here in town; he wasn’t any bigger than a cake of soap after a hard day’s washing. And his nickname was “Rabbit.” Rabbit played for almost all of the dances, and could he play! I think he played entirely by ear.

HUGHES: Piano, of course.

BREWER: Piano, mm-hmm. You really had to dance when Rabbit started to play, because it was that type of music.

HUGHES: What about the doings over at The Breakers and the Royal Poinciana. Didn’t they get around in wheelchairs that were peddled or something?

BREWER: Before the wheelchairs came into existence, Flagler imported a lot of jinrikishas from Japan.

HUGHES: Oh, no! [laughs]

BREWER: But they didn’t last too long, because they had quite a few accidents with them. Sometimes the passenger was heavier than the Negro pulling them, and over they would go. So after a few lawsuits, Flagler decided that was it. So then he started with the wheelchairs.

HUGHES: [laughs] What a picture, the poor guy up in the air!

BREWER: I did hear a story about this fella. He’d evidently had a little bit too much to drink, and he ordered the colored fella to take him out on this dock. So the colored fella took him out on the dock, which, by the way, was a little narrow. When he went to turn the jinrikisha around, he lost balance and over went this fella in the lake. [both laugh]

HUGHES: And then came the wheelchairs with them peddling from behind.

BREWER: Then came the wheelchairs, yes. And then, of course, after Flagler built the Whitehall in the early 1900s, they had a railroad bridge. They had a lot of private cars, of course. Flagler had his private cars, and so many that stopped at the Poinciana Hotel had private cars. The private cars went over the railroad bridge and stopped at the south end of the Poinciana. But after Flagler built his home, he didn’t want the trains coming between his home and the Poinciana. So then the new bridge was built and the cars came in on the north end of the Poinciana.

HUGHES: [laughs] Oh, I see!

BREWER: But the tracks were still left there, in fact, I think are still there today. Then they had what they called a little “mule car” that ran between the Poinciana and the Breakers, just a little coach pulled by a mule.

HUGHES: Gee, there again would be something to hunt for, that coach.

BREWER: I have a picture of it. Mm-hmm. Oh, it was a delight to the children, because they would let the children drive the mule. They thought, of course, they were driving the mule. All the poor mule could do was stay in the—

HUGHES: Did they charge for it?

BREWER: Yes. I don’t know whether it was five or ten cents.

HUGHES: And wasn’t there a ferry between?

BREWER: Yes, in fact, they used to charge when you went over the bridge.

HUGHES: Oh, did they?

BREWER: Oh yes, it was a toll bridge. You had to pay—

HUGHES: Even if you walked? How much?

BREWER: Oh, it was five or ten cents, I can’t remember. But I remember so well [our] delivery truck. We called it the “bun wagon” at the bakery. And we used to pile into that thing, and my brother would drive it. Maybe there’d be half a dozen of us inside and of course, when Frank would get to the bridge-tender, he’d pay the bridge-tender his ten cents. Then when we got over on the other side, there’d be a half a dozen or so of us pour out and we just thought that was more fun, you know, to cheat the man.

HUGHES: Was there a drawbridge?

BREWER: Yes, there was.

HUGHES: Anybody get stuck in it there?

BREWER: Oh, I suppose every once in a while, but I can’t remember any particular instance. I do remember when they first put up the Royal Park Bridge, the bridge leading into Royal Park. They had just completed it when the spans collapsed. Just a day or two before it was supposed to be opened, some engineering defect—it was quite a calamity.

HUGHES: I should think so. I was just thinking they probably didn’t have a bridge-tender all night long, because they didn’t have that much traffic going up and down, in which case they must have left the draw open.

BREWER: No, the bridge-tender and his wife lived in the little cottage there on the bridge, so they were there all night long.

HUGHES: Oh, I thought maybe they had gone by. Well, are there any other things I haven’t talked to you about that you remember?

BREWER: [pause] Well, I remember when I was real, real young, they used to have taffy parties, which they don’t have anymore. Mother would fix the taffy and get it all ready to pull, and we’d all stand around pulling it. And sometimes at the end of the afternoon, the boys would get a little rambunctious, and we’d have more taffy in our hair than we—[laughs]

HUGHES: [laughs] Oh, and that was hard to get out, too, wasn’t it?

BREWER: Yes, indeed it was! Sometimes you’d almost have to cut it out!

HUGHES: This is probably the way the girls’ bobbed hair originated, was to get rid of the taffy.

BREWER: I think perhaps that was so, because then we’d have “pound parties.” Everyone would bring a pound of something, cookies or candy or fruit. You don’t ever hear of them anymore.

HUGHES: No, no. It’s a real good idea.

BREWER: It is! Excellent idea. I remember Mrs. Saunders had the first dressmaking establishment, at the corner of Datura and Olive, for a good many years. Back in those days, of course, you couldn’t buy ready-made things. But her clientele was mostly people from the Poinciana and The Breakers, because if there ever was an artist, she was. I remember that long, long table that she had covered with green felt. And if you went in there, didn’t make any difference whether you were size 14 or 42, she’d take one look at you and spread the cloth on the table and cut it out—never cut by pattern. You’d pick out the picture of the dress that you wanted. I remember one couple in town, [the young man] came home from college and this couple decided to get married, and she went in about eight o’clock in the morning and said, “Miz Saunders, we’re going to get married at eight o’clock. Do you suppose you could make me a wedding dress?” She said, “Indeed, I could,” and she did. The wedding dress was ready at five o’clock in the afternoon.

HUGHES: [laughs] She was an artist, huh?

BREWER: Yes, she was.

HUGHES: Well, most people used patterns. Who was making patterns? Butterick?

BREWER: [pause] I think it was Butterick at that time, mm-hmm.

HUGHES: They had no hairdressing facilities.

BREWER: Oh, no, no.

HUGHES: In fact, girls didn’t curl their hair, did they?

BREWER: I was very fortunate. I had curly hair, so it wasn’t ever a problem with me.

HUGHES: [pause] Anything else?

BREWER: Well, unless you want to know the names of some of the early hotels.

HUGHES: Oh, I’d love to know the names of anything.

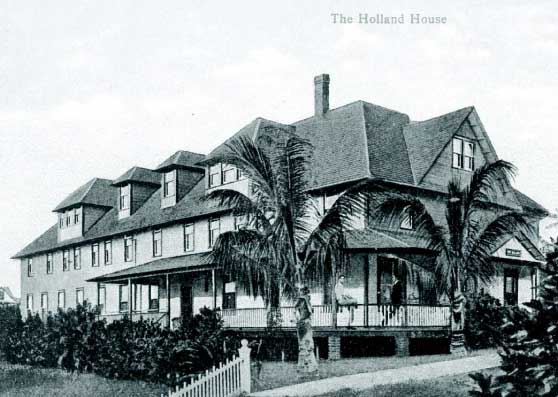

BREWER: Early hotels was the Palms and the Seminole, which was later called the Lake Park Hotel, which fronted Narcissus Street. And then Trevette Lockwood’s father had a hotel called the Holland House, which is about the site of the Pennsylvania at the present time. And then Mrs. Benjamin Cook had the Keystone Hotel, which was on Datura between Dixie and the railroad. The Tiffany House was on North Dixie. And the Minaret Cottage was between Evernia and Fern.

HUGHES: How were things delivered?

BREWER: The grocery stores had delivery bicycles with a great big basket or crate on the front of it. Sometimes they’d even have a double crate if the deliveries were heavy. And I remember so well, my brother working at this grocery store, and they put a little bit too much weight on the front of the bicycle, so when he got on the bicycle, the bicycle went end over end and he with it, with a fifty-pound bag of flour, which I think ripped open.

HUGHES: [laughs] They used to call those half-barrels, didn’t they, or something? Wasn’t fifty pounds a half a barrel?

BREWER: I think so, uh-huh. Bicycles were the mode of travel, and they used to have bicycle racks down the center of the street, and the merchants would advertise on these racks, you see, have their name printed on there.

HUGHES: Did they have races too?

BREWER: Oh yes, they had races. And I can remember one Labor Day, they had a big celebration on Munyon Island, in the north part of the lake. We all went up there, and they had sack races and egg races—you carry a spoon in your mouth with an egg in the spoon—and three-legged races.

HUGHES: Was there a newspaper here?

BREWER: Yes, the very first newspaper here, if I remember rightly, was The Tropical Sun.

HUGHES: Who ran that?

BREWER: I’m pretty sure it was Guy Metcalf.

HUGHES: And then anything after that?

BREWER: Well, Mr. Currie had a paper that he got out, I think called Currie’s Megaphone.

HUGHES: You are a fountainhead of information.

BREWER: The very first library was in a building right at the end of the city dock.

HUGHES: That’s close to the present one, isn’t it?

BREWER: Mm-hmm, yes, very close to the present one. Vesta Wilson, who later married Ben Potter, had the first kindergarten in town, in my mother’s building on Clematis Avenue.

HUGHES: Oh? They gave the kids cookies to keep them quiet, huh?

BREWER: Yeah, mm-hmm. And the very first Post Office that I remember was in the Palms block, and then it was later moved to Datura Street. And then from Datura Street, [to] where Belk’s store is now, fronting on Olive, and then to the present location.

HUGHES: How much did a loaf of bread cost in your mother’s bakery?

BREWER: A loaf of bread cost five cents, and if you bought a quarter’s worth, you got six for a quarter.

HUGHES: Pound loaves?

BREWER: Yeah, mm-hmm.

HUGHES: They didn’t have any slicing machines. You had to slice them at home?

BREWER: Oh, no, no slicing machines. [E. R.] Bradley had the Beach Club at the time over in Palm Beach and a very fancy restaurant connected with it. Mother had all of his business, which was, of course, a little bit different. We had special pans to cook his bread in, because he served these big sandwiches. And I remember every once in a while, I would fix up one of our front windows with just the things we made for the Beach Club.

HUGHES: Oh, you made other things beside bread?

BREWER: Oh yes, fancy cake and cookies and whatnot.

HUGHES: How many varieties of bread were there?

BREWER: We had white bread, graham bread, whole wheat, rye, Vienna bread—the Vienna and the rye were cooked on the hearth . . . besides rolls. Later on, I had a brother that went to Boston and worked in a bakery up there, so when he came back, we introduced baked beans. The baked beans was a specialty on Saturday night, and I can remember people lining up for those baked beans. Then Saturday was the day for coffee cake and cinnamon buns—specialties.

HUGHES: You couldn’t have things like éclairs and charlotte russe? No refrigeration.

BREWER: Oh, no, no refrigeration.

HUGHES: Did your mother have special cookies, sugar cookies or—

BREWER: Oh, we had all kinds of cookies, ten cents a dozen. And when my mother went up to twelve cents a dozen, a penny a piece, my, they did howl! In the wintertime, the tourists would come in. We had two long counters on each side of the store, and you’d walk yourself to death ‘cause they’d want one cruller, one sugar cookie, one cinnamon cookie, one nut cookie—

HUGHES: [laughs] And something from over there!

BREWER: And something on this side, see. So for twelve cents, they’d get a sample of everything that was in the store.

HUGHES: [laughs] Where’d she get her supplies from? They had to come in by train, from where?

BREWER: Jacksonville. And believe it or not, water transportation at that time was in Miami, and my mother would order her flour from Jacksonville and the freight on a barrel of flour cost Mother more to be delivered in West Palm Beach. It could go down to Miami and they would get it cheaper than Mother would here, because they provided water transportation down there.

HUGHES: Oh, for heaven’s sake. Well, freight has always been a problem. You got anything else to share?

BREWER: Oh, I might just tell you this: I think the biggest event of our lives was when we got our first bathtub. I was a little bit of a thing and remember so well. I was so proud of that bathtub that the first night we had it, I put blankets in the bottom of it and a pillow, and I slept in the bathtub until almost morning. I must have turned over and knocked the side of it, and it woke me up. And it scared me so that I got out and went to my bed.

HUGHES: How did you bathe before that?

BREWER: With tin tubs. And when the weather was cool, we had a little old stove. Had to heat the water on the stove, of course. You can imagine with so many people taking baths—and then we had, if I remember right, an old wood stove, and it had a reservoir tank on the back of it. And besides that and the water that we heated on top of the stove, that was it.

HUGHES: [laughs] I’m glad I didn’t live in the tin tub days!

BREWER: Oooh, I’m telling you.

HUGHES: I never would’ve made it! Well, I want to tell you, Mrs. Brewer, you have been a veritable fountainhead of information.

BREWER: Oh, I wished I’d had more time, maybe I could’ve been a little bit better.

HUGHES: I’m coming back next week, and I’m going to call you, and you think of things to tell me in the meantime.

BREWER: Well now listen, turn that off. I do want to—.

END

Historical Society of Palm Beach County

You might also enjoy

A Celebration of Pride

Advertisement announcing the opening of H.G. Roosters in 1984. Celebrating

Black Cultural Heritage Trail

Learn of the Rich Cultural Heritage of Palm Beach County

The Conchtown Rumrunners

The Conchtown Rumrunners Behind the Palms, Episode 2 Volstead Act

Ste

Ste

Wonderful history. You

Might be interested in the historic Pacetti House and hotel. Now owned by Lighthouse Association of zoo crew Inlet.