This article from the 2010 fall issue of Tustenegee is by HSPBC’s former Archivist, Steven Erdmann. For proper context, please note the original publication year of all reprinted articles here; they receive only minimal editing.

by Steven Erdmann

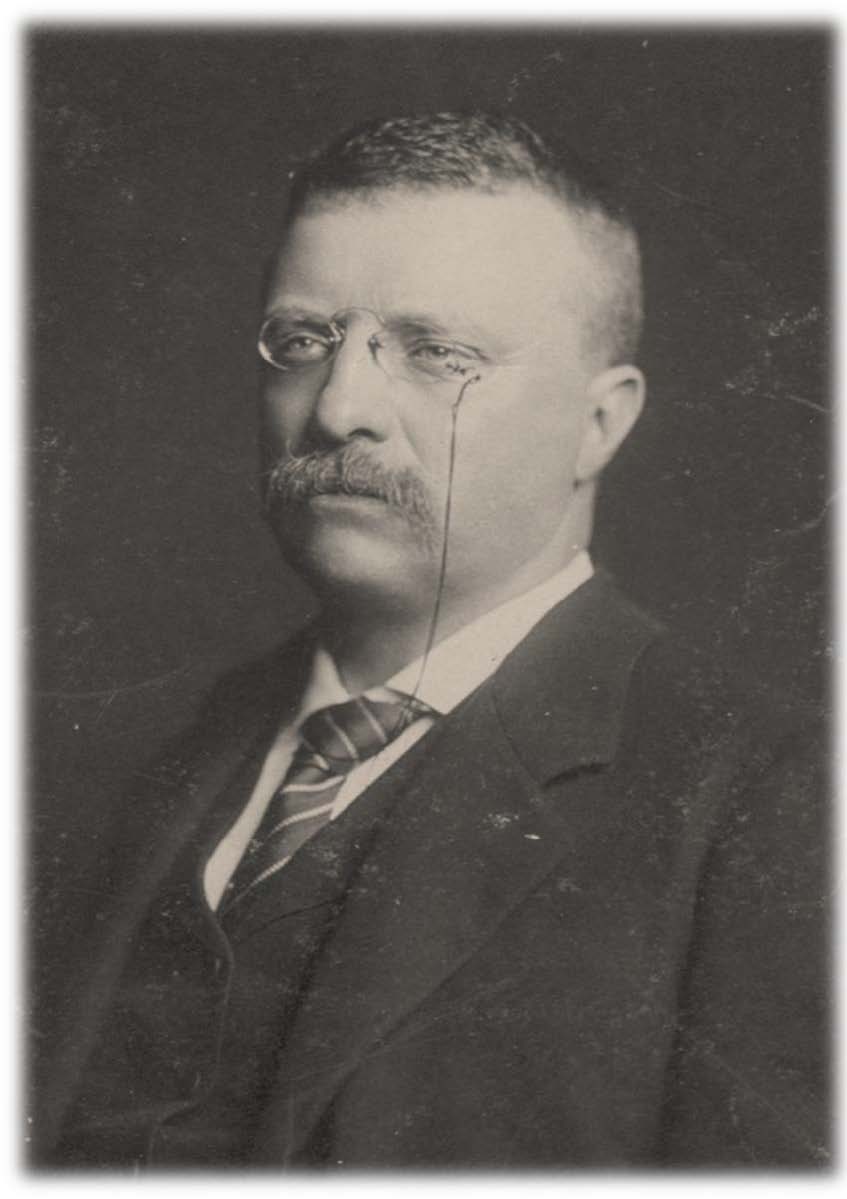

As has occurred many times throughout history, the efforts of a single individual become a galvanizing force that changes events. In the case of the ‘Feather Wars’ that person was Theodore Roosevelt, the twenty-sixth President of the United States. As William T. Hornaday, then director of the New York Zoological Park wrote in 1913, “When the story of the national government’s part in wild-life protection is finally written, it will be found that while he was president, Theodore Roosevelt made a record in that field that is indeed enough to make his reign illustrious.” In 1903 with the simple phrase, “I So Declare It,” Roosevelt began the modern era of environmental protection.

when he made his decision to establish Pelican Island

as a national wildlife preserve, 1903. Courtesy Library of Congress.

The ‘Feather Wars’ encompass a period of time from the late 1800s through the early twentieth century during which a market demand for exotic bird feathers was countered by both political and social activism. The use of feathers and exotic plumage for personal decoration can be documented at least three thousand years. From the fans of Egyptian pharaohs to the plumed helmets of Roman military officers, feathers have been used to indicate status and rank. Marie Antoinette has been credited for beginning what turned into a fashion craze in Europe of decorative plumage that had global consequences.

By the late 1800s the industrial revolution was in full development in the United States. One person killing a bird and mounting its feathers on a hat had little effect on the natural environment. But factories manufacturing shotguns that could bring down thousands of birds as resource material for the millinery industry is a different story. By 1900, millinery companies in the United States employed over 83,000 workers.

Manufacturing plants also built printing presses. Mass produced women’s fashion magazines featured exotic feathers adorning hats, gowns, capes, and parasols. Women’s demands for feathered creations produced a market demand for great quantities of prized plumage. “The desire to be fashionable led scores of thousands of women to milliners for something eye-catching and elegant,” wrote historian Robin Doughty in Feathers and Bird Protection. By the turn of the twentieth-century it is estimated that more than five million birds a year were being killed to supply the booming American millinery trade.

What began in Florida with pioneer residents supplementing the family’s income by shooting birds and selling the plumes progressed to market hunters traveling to the state to harvest ever larger caches of birds. The most coveted and highly valued plumage occurs during the mating and nesting season, therefore that’s when they were hunted. Two generations were lost with each with each attack on a rookery – immature eggs and young birds were left to die of starvation. With dwindling bird populations the price of plumage increased exponentially until an ounce of snowy egret feathers was worth twice that of gold; and so more hunters journeyed to Florida to strike it rich.

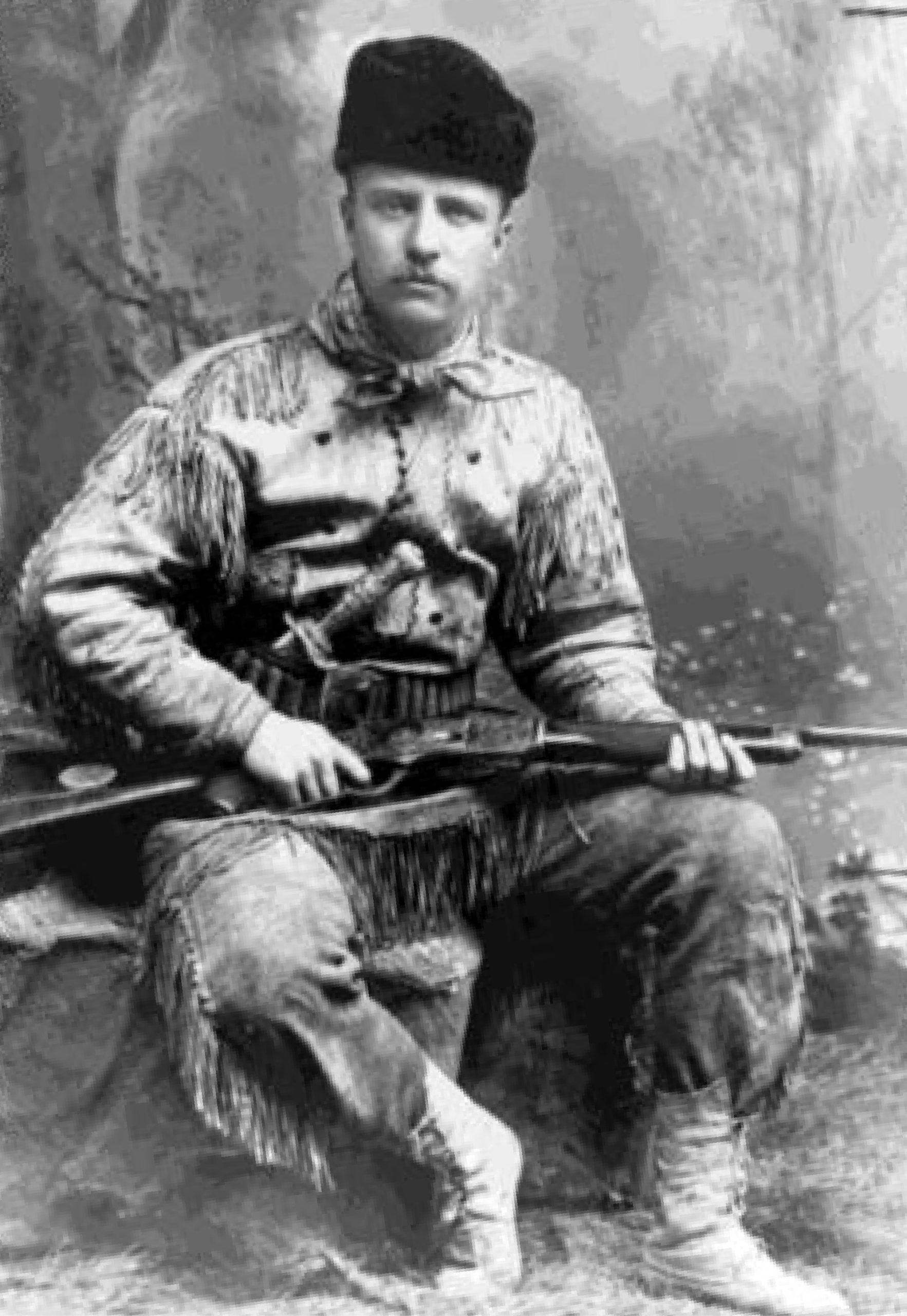

Although many people worked to end the slaughter, only one person ultimately had the power to bring an end to the carnage. Theodore Roosevelt was born in 1859 to a wealthy Manhattan, New York family. A caricature image of Roosevelt exists in the public mind that does not begin to describe the man he became. As a child he was fascinated by the natural world around him, but particularly by birds. “It was the world of birds – birds above all – that burst upon him, upstaging all else in his eyes,” historian David McCullough wrote in his book, Mornings on Horseback.

A favorite boyhood book of Roosevelt’s was the Boy Hunters, the story of three brothers hunting for a white buffalo written by Captain Mayne Reid. Unlike other books of the time, Reid included the proper Latin names for wildlife and plants. This inspired Roosevelt to begin keeping diaries recording his attempts to properly identify every bird in the Manhattan area. He learned bird taxidermy from one of John James Audubon’s assistants and a room in young Roosevelt’s home became The Roosevelt Museum, containing taxidermy specimens of the birds of New York.

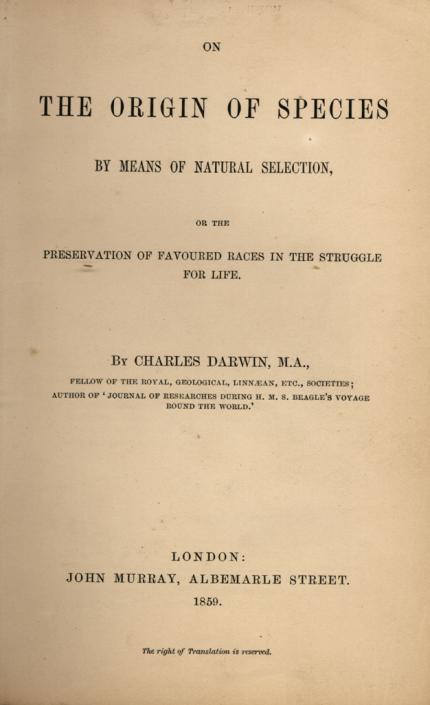

Roosevelt’s father was one of the founders of New York’s American Museum of Natural History. As the child of a large donor, he had nearly free access to the Museum’s laboratories. An assistant at the Museum gave a teenaged Roosevelt a copy of Charles Darwin’s On Origin of the Species to read. He often said that it changed his outlook on the world thereafter. He tried to understand the multitude of bird species throughout the world from an evolutionary perspective, reading all he could by noted ornithologists. His early curiosity about the natural world combined his with exposure to scientific inquiry led Roosevelt to make decisions that helped stop the feather trade.

By the early 1900s, Pelican Island, in the Indian River Lagoon across from the town of Sebastian, had the last breeding colony of brown pelicans on Florida’s east coast. It had long been the intention of Frank Chapman, Curator of Ornithology at American Museum of Natural History, to purchase Pelican Island and create a bird sanctuary. He worried though that representatives of the millinery industry would attempt to outbid him. In 1886 Chapman had a letter to the editor published in Forest and Stream (precursor to Field and Stream) entitled, “Birds and Bonnets.” He was outraged that three-quarters of the women’s hats he observed in Manhattan were adorned with exotic feathers (he actually did field observation of this kind and tabulated tables by bird species). Chapman had an early understanding of a concept that wouldn’t be named for decades – biodiversity. Chapman insisted that the habitat for breeding and nesting birds in Florida had to be preserved.

Roosevelt first learned about Pelican Island while working on his natural history degree at Harvard University from the published field notes of Dr. Henry Bryant. In 1859 Bryant recorded his observational notes at Pelican Island while retained as an ornithologist by the Boston Society of Natural History. Before sailing to Cuba during the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt had spent hours studying brown pelican habits from his station on Tampa Bay and was fascinated by these birds. While in Tampa he observed bird carcasses piled twenty yards high near the port rotting in the sun from plume hunting activity. The image haunted him.

Roosevelt’s political effort to protect bird rookeries in Florida began in March 1903, eighteen months into his presidency following the assassination of William McKinley. As one of the honorary founders and officers of the Florida Audubon Society, he wanted to strengthen the reach of the U.S. Biological Survey in Florida. To Roosevelt, “the Union victory in the Civil War, in fact, meant that the U.S. federal government had emerged as the principal proponent of national reform movements like conservation.” (Douglas Preston)

In 1900 the Lacey Act, which made it illegal to transport protected birds across state lines, was passed and signed into law. The following year Florida passed the Model AOU (American Ornithologist Union) Law protecting non-game birds. The AOU had wisely come to the conclusion that if they created template verbiage it had better chances of getting these laws passed. State legislation was necessary to set up categories of protected non-game birds for the Lacey Act to function as envisioned. A larger problem for Chapman’s vision loomed; Pelican Island had not been surveyed by the U.S. General Land Office (GLO). William Dutcher, then Chairman of the AOU, had a survey commissioned. With the survey about to be filed, it came to light that homesteader’s applications had to be given preference when GLO land was sold.

By 1903, Roosevelt was an old-hand at American politics. Though he came to the presidency by the assassination of William McKinley, he had previously been the U.S. Civil Service Commissioner, a member of the Board of Police of Commissioners of New York, and Governor of New York. He understood how the structure of government functioned. In March 1903, a meeting of minds took place at the White House – Roosevelt, Frank Chapman, and William Dutcher. As Douglas Brinkley wrote of the meeting in Wilderness Warrior, “after listening attentively to their description of Pelican Island’s quandary, and sickened by the update on the plumers’ slaughter for millinery ornaments, Roosevelt asked, ‘Is there any law that will prevent me from declaring Pelican Island a Federal Bird Reservation?’ The answer was a decided no; the island, after all was federal property. ‘Very well then,’ Roosevelt said with marvelous quickness, ‘I So Declare It.’

Defenders of short-sighted men who in their greed and selfishness will, if permitted, rob our country of half its charm by their reckless extermination of all useful and beautiful wild things sometimes seek to champion them by saying that “the game belongs to the people.” So it does; and not merely the people now alive, but to the unborn. The “greatest good for the greatest number” applies to the number within the womb of time, compared to which those now alive form but an insignificant fraction. Our duty to the whole, including unborn generations, bids us to restrain an unprincipled present-day minority from wasting the heritage of these unborn generations. The movement for the conservation of wild life and the larger movement the conservation of all our natural resources are essentially democratic in spirit, purpose, and method. Theodore Roosevelt, A Book-Lover’s Holidays in the Open (1916) |

During the remainder of his presidency, Roosevelt set aside over 234 million acres of the United States and U.S. held territories as national parks, national forests, and wildlife refuges. The tide had turned in the Feather Wars. Not only in terms of national wildlife refuges, but in the sheer magnitude of protected habitat to support avian life. Additional legislation was combined with such social activism as the women’s suffragists’ movement, taking their lead from Queen Victoria in Great Britain who had made a pubic proclamation denouncing ornamental feather use. But it was Theodore Roosevelt’s executive declarations that protected wildlife habitats, such national treasures as the Grand Canyon, and Florida’s shore birds.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County

You might also enjoy

Stories of Rescue

Stories of Rescue Now on Exhibit on the 1st Floor

Endless Summer: Palm Beach Resort Wear

Endless Summer: Palm Beach Resort Wear November 9, 2023 –

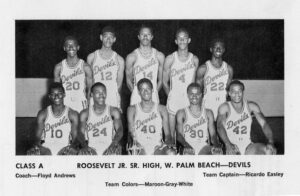

More Than a Game: Champions in the midst of Desegregation

Back to all More Than A Game: Champions in the